Miami & Erie Canal, Warren County Canal, and Cincinnati Subway

Miami & Erie Canal, Warren County Canal, and the Cincinnati Subway

Introduction

Studying transportation history is much like studying archaeology.

Multiple layers of strata, whether literal or figurative, must be

peeled back to reveal the history beneath. These layers tell us

about technology, urban development, industrialization, and cultural

priorities as they change over time. In the temporal hierarchy of

transportation, the canal is one of its most ancient systems, preceded

only by primitive dirt trails and cart paths. The earliest canals

were used for irrigation of agricultural fields, but the ancient

Egyptians, Chinese, and Greeks built canals for drinking water and transportation. They provided much improved ability to

move bulk cargo than wagons and pack animals. For this reason,

they became a mainstay of early transportation infrastructure.

It must be understood that even large waterways

like the Ohio River are not naturally navigable at all times of the

year. Dry periods would make the river too shallow for boats to

pass, and floods would make it too dangerous. Even the Mississippi

River doesn’t have enough depth and flow to be naturally navigable

north of St. Louis. On the Ohio River, the falls at Louisville

were only passable by riverboats during periods of high water.

Indeed, these cities are where they are because of the navigational

challenges that required offloading cargo and passengers to different

modes. Commerce thrives at such transfer points.

Nevertheless, there’s great pressure to extend transportation routes

further inland to tap fertile farmland, natural resources, and new

markets. In Louisville’s case, a short canal was constructed in

1825 to bypass the falls and allow boats passage, no matter the river

level. Little was done to improve navigation beyond that until the

late 19th and early 20th century when a series of wicket dams were

built to raise the water level across the entire river, essentially

turning it into a series of shallow lakes.

While the Ohio and the Upper Mississippi River would be further

canalized with larger and more elaborate dams in the middle 20th century to accommodate

ships and barges, navigation was and still is limited to the existing

route of those rivers. In the early 19th century, finding a way to

transport agricultural products across the Appalachian Mountains

to the growing markets of the east coast was critical. No rivers flow across the mountain range, and overland

routes were too slow and expensive for bulk commodities. This is

but one reason many farmers turned to distilling whiskey or other

spirits from their harvested grain, since it had a higher value, less

bulk, and wouldn’t spoil on the month-long journey to New York, Boston,

or Philadelphia. When the Erie canal opened across New York State

in 1825, it linked the Hudson River with Lake Erie, providing a shipping

route from northern Ohio and southern Michigan to the Atlantic

Ocean. Travel times were cut in half, and the tonnage that could

be pulled by a single team of mules or horses increased to such a degree

over pack mules and wagons that costs dropped by a factor of

four.

Construction

The Erie Canal was all well and good for northern Ohio, but there was no

equivalent route to transport grains from the fertile lands of western

and central Ohio to Lake Erie, or southward to the Ohio River for

shipment to the growing cities of Cincinnati, Pittsburgh, Louisville,

New

Orleans, or St. Louis. The Ohio River and Lake Erie watersheds do

not mix, and thus no rivers traverse the whole state north to

south. A man-made waterway was the best option to link the Ohio

River with Lake Erie to create a crisscrossing network of transportation

routes. Developing such transportation links was critical to

supporting the Industrial Revolution, which required raw materials,

fuel, and a means of distributing finished products. This sparked a

wave of canal fever in the early 19th century that saw new routes

developed not just in New York and Ohio, but also Indiana, Illinois,

Pennsylvania, and much of the eastern seaboard. The United

Kingdom, Belgium, the Netherlands, France, and Germany also developed

extensive networks of canals to support growing industries. US

states were anxious to get on this bandwagon.

The Ohio House and Senate had worked for two decades to pass legislation

authorizing a canal, and they finally succeeded on February 4, 1825 after it became evident that the Erie Canal was going to be a huge boon to New York state. This new Ohio canal system would be

largely state-funded. Money was raised by selling bonds, and land

near the canals was sold or leased. Engineer James Geddes, who

worked on the Erie Canal, was hired to design a network for

Ohio. Two waterways would be constructed, the Miami Canal from Dayton to

Cincinnati, and the Ohio & Erie Canal from Portsmouth to Cleveland.

This system would provide the interior of Ohio with new travel routes

that effectively extended to the major Atlantic port of New York City,

as merchants could ship goods through Lake Erie, the Erie Canal, and the

Hudson River to New York.

While the Ohio & Erie Canal was a cross-state venture with multiple

branches, the Miami Canal was originally planned to run only between

Cincinnati and Dayton. The upper reaches of the Great Miami River

watershed would eventually become prime agricultural land, but in the

early 19th century it was sparsely settled and slow growing compared to

the Cincinnati-Dayton corridor. Farther north, the Great Black

Swamp stretched across most of northwest Ohio from Fort Wayne to Toledo,

an even more difficult to traverse and less developed area. So the

focus was on the 66-mile route between Cincinnati and Dayton.

|

|

This early

painting of downtown Cincinnati as seen from Mt. Adams in 1841 shows

the Miami & Erie Canal running down what would later become

Eggleston Avenue.

|

At this time in the state’s history there were no construction companies

big enough to carry out such a monumental project as a canal. So

after surveying and land transfers were complete, the state divided the

construction project into numerous sections for local contractors to bid

on. A section could be as small as a single lock, culvert, or aqueduct,

though the typical section length was approximately half a mile.

As sections opened up for bidding, dates of completion were dictated by

the state to ensure speedy construction. A ground breaking

ceremony was held south of

Middletown on July 21, 1825, and the first water flowed into the canal

on July 1, 1827. By August of that year, the canal between

Middletown and Hamilton was open. It was finished to Cincinnati in

December, 1827, but it took four months for enough water to fill the

canal to float any boats to the city. By January 25, 1829, the

full length of the Miami Canal became operational, connecting Dayton to

the Ohio River. It was informally nicknamed the Rhine in downtown

Cincinnati

due to the large number of German immigrants living in the neighborhood

north of the canal. Since many of these residents walked to work

downtown, they were said to be going "over the Rhine" which led to the

neighborhood taking on this name.

On February 22, 1830, the Ohio General Assembly incorporated the Warren

County Canal Company to construct and operate a branch canal to

Lebanon. The seat of Warren County, Lebanon is at the intersection

of the road from Cincinnati to Columbus, and the road from Chillicothe

to Oxford. The city sits on high ground though, so transportation

options were limited, and a branch canal seemed like a good way to

link it to other markets. Work progressed slowly on the canal and

the company eventually acknowledged it could not complete it. On

February 20, 1836, the General Assembly ordered the Canal Commissioners

to take possession of the unfinished project. The Warren County Canal

was made completely navigable in 1840. Built to the same standards as

the Miami & Erie, it began at Middletown at what is today the

Middletown Transit Station at Reynolds Avenue. The lower end of the

canal was supplied by a feeder

off the Miami & Erie Canal three miles north at lock #30 (Lower

Greenland).

From Middletown, this canal went southeast over land filled with sand

and gravel deposited by the Wisconsinan Glaciation 14,000 to 24,000

years ago. This geology meant the canal leaked considerably.

Two aqueducts carried the canal over Dick's Creek, but the aqueducts

were built too shallow for use by heavily laden canal boats. The

canal continued its path southeast into Turtlecreek and Union townships

along the path of Muddy Creek to about Hageman Junction at US-42.

There it turned northeast, paralleling Turtle Creek, which it crossed

on an aqueduct, approximately the route later taken by the Cincinnati,

Lebanon & Northern Railway. At Lebanon, there was a turning basin in

the space bounded by Sycamore Street, South Street, Turtle Creek, and

Cincinnati Avenue. The canal was fed with water from the North and East

Forks of Turtle Creek at Lebanon.

Lebanon is 44 feet above the elevation of the Miami & Erie Canal at

Middletown, so six locks, each 90 feet long and 15 feet wide, were

necessary to overcome this. Lock #1 was at the foot of Clay Street in

Lebanon. Lock #2 was a short distance downstream, still in Lebanon. Lock

#3

was about a mile southwest of Lebanon near Glosser Road and Turtle

Creek. Lock #4 was about three miles southwest of Lebanon near the

confluence

of Muddy Creek and Turtle Creek. These locks raised and lowered boats a

total of 28 feet. Locks #5 and #6 were just east of where

the canal entered the Miami & Erie in Middletown, they were most

likely on the hill between Curtis and Garfield, and they raised and

lowered boats the remaining 16 feet.

Not long after the Miami Canal opened, the Wabash Canal in Indiana began

construction in 1832. It would run between Evansville and Toledo

via Terre Haute, Worthington, Lafayette, and Fort Wayne. It

reached Lake Erie by following the Maumee River through the Great Black

Swamp. After political lobbying, Ohio agreed in 1831 to build the

Miami Extension Canal, which would run from Dayton to the Wabash &

Erie Canal just south of Defiance (Junction), creating a through route

to Lake Erie. Work on the extension started in the spring of 1833

and it was completed as far north as Piqua by June 20, 1837. The

first canal boat was launched the next day, and it reached Piqua on July

5 after a one-day delay because of a lack of water north of Troy.

Piqua served as the northern terminus of the extension until 1842 when

additional sections to the north started opening. By June 1845,

the entire Miami Extension Canal was finished, and travel from

Cincinnati to Toledo became possible. Of the 250 mile length of

the finished canal, only four miles were in slackwater, which were

dammed segments of the Maumee River. In 1849, the Miami Canal,

Miami Extension Canal, and Wabash & Erie Canal north of Junction

were merged and renamed the Miami & Erie Canal.

Cincinnati was also served by a second canal running to the fertile

farmlands of southeast Indiana. Ground was broken for the

Whitewater Canal on September 13, 1836, on a route between Lawrenceburg

and Hagerstown. In 1838 the Cincinnati & Whitewater Canal

broke ground to connect Cincinnati to the Whitewater Canal at

Harrison. This second canal opened for business on November 28,

1843, and the main canal finished construction in 1847. Though

built for a similar purpose as the Miami & Erie, the two canals did

not have a connection to one another, since the Cincinnati &

Whitewater Canal terminated at Pearl Street (today between Pete Rose Way

and 3rd Street) and Central Avenue near the riverfront at a much lower

elevation than the Miami & Erie, and it had no direct connection to the

Ohio River. More information can be found in the history of the

New York Central/Big Four Railroad's CIND and Whitewater divisions.

How The Canal Works

While a canal may look like a small river or creek, it is actually more

like a series of long narrow lakes. There is water flow, but the goal is

to create a pool with a consistent depth and width that has minimal

current. Excess flow would cause undesirable drag on boats,

erosion of the banks, and it would deposit sediment where the current

slackens. Also, a level water surface and canal bottom is

necessary to maintain the tight depth clearance needed. The

overall shape of the canal channel and earthen berms is called the canal prism. Dimensions were 40 feet wide at the water line,

approximately 28 feet at the base, and the depth would be at least four

feet to allow a maximum draft of three and a half feet for canal

boats. North of Dayton to Junction the width at the water line was

50 feet, and from Junction to Toledo it was 60 feet. Why exactly

the canal used a wider prism farther north is unclear.

Since building a canal below existing grade would subject it to flooding

and sediment from rains and nearby rivers and creeks, they were

generally built so

the bottom of the canal was near existing grade, and the berms on either

side would act as dikes or levees to hold in the water. This way,

any perpendicular streams or rivers could flow underneath through a

culvert pipe or aqueduct. One of the berms would have a towpath,

which was specified to be 10 feet wide. It was to allow horses,

mules, and their handlers to pull the canal boat with a long rope.

The towpath was most often on the lower side of the underlying terrain,

and thus when paralleling a river, on the river side. The extra width

of the berm provided more resistance to the weight of the water

behind it.

The opposite berm bank, or heelpath, was only six feet wide. The

top of the towpath and heelpath were six feet from the base of the

canal, allowing two feet of extra height to accommodate overflow and

splashing. Occasionally the towpath or heelpath

would dip down to allow excess water to overflow out the side in a

controlled manner where the embankment was reinforced to resist

erosion. At several points along the canal there were more

elaborate spillways to discharge excess water.

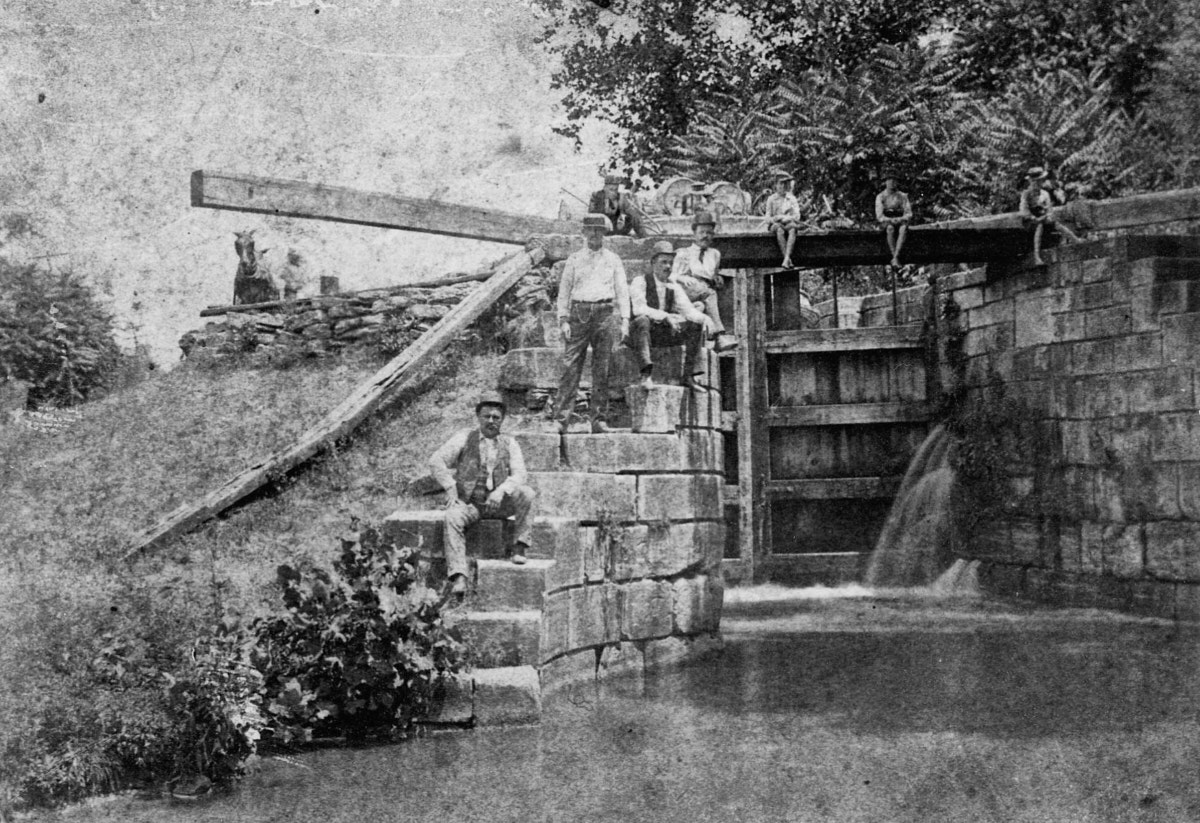

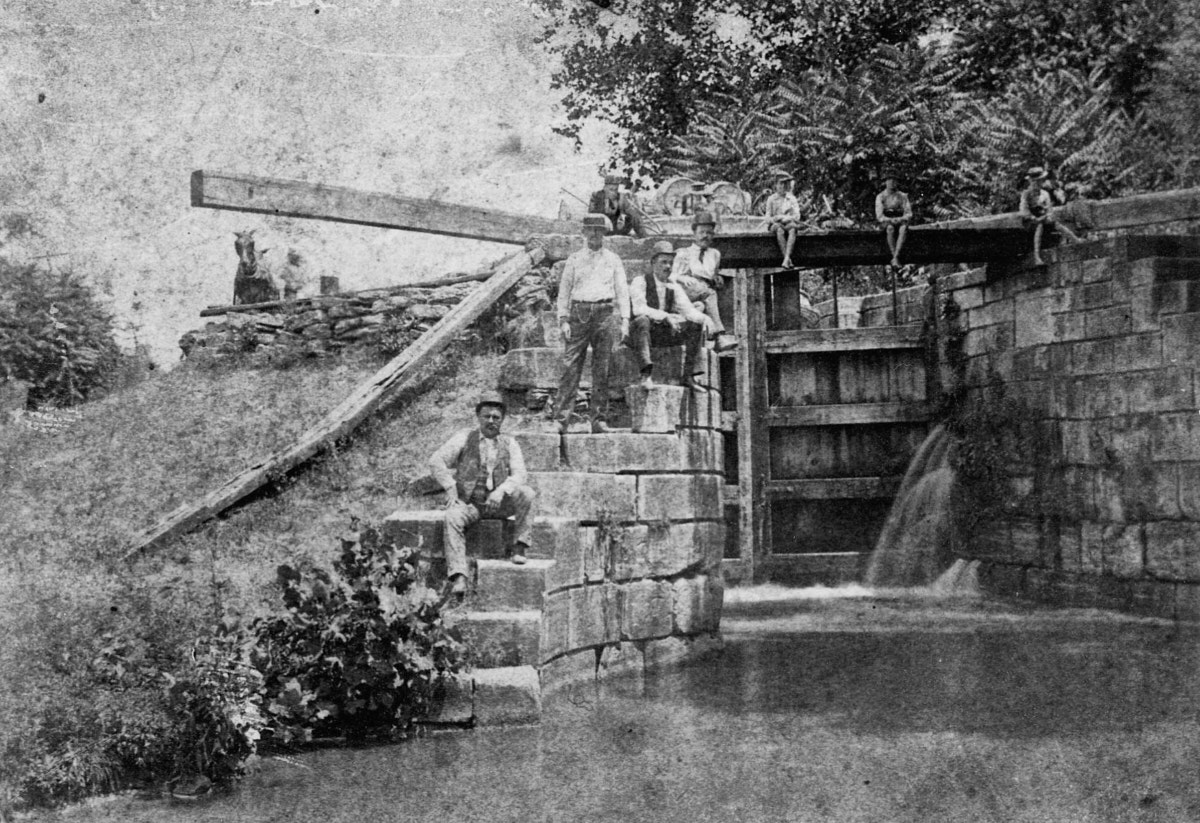

|

|

The Excello lock was the first

constructed on the Miami & Erie Canal. Note the large stone

blocks and the wooden gate holding back the water.

|

Before laborers could even begin to build the canal prism they first had

to remove any stumps, roots, rocks, and topsoil. This process was known

as grubbing. Although labor intensive, grubbing was necessary for the

integrity of the canal prism. Leftover roots could sprout through the berm bank or towpath, creating breaks in the

prism. In areas where the soil was particularly porous, the bed of

the channel was lined with puddle, a mixture of clay and water

intended to slow or stop water from percolating into the ground. Puddle

was also used as a bed for foundation timbers, which were an integral

component to stone canal structures. The Warren County Canal

either didn’t use puddle or it wasn’t thick enough to prevent

significant exfiltration.

While a single long narrow lake would be the simplest to navigate, it is

not the simplest to build. Because land is almost never entirely

flat, a system of locks had to be built so the canal wouldn’t need

numerous deep cuts, tunnels, or elevated aqueducts. A canal would

be of little use in a tunnel hundreds of feet underground or on a high

aqueduct with no easy way to reach it to load and unload cargo.

At Spencerville, between Delphos and St. Marys, a deep cut of up to 52

feet was still necessary to breach a one and a quarter mile ridge and avoid the need

for a tunnel or several locks. Even if the land was as flat

as possible, the Ohio River at Cincinnati is roughly 100 feet lower than

Lake Erie, so a perfectly flat connection between the two bodies of

water is not possible. Also, the Loramie Summit is a 20 mile

plateau between Lockington, north of Piqua, and New Bremen, which is 395

feet above the level of Lake Erie, and 510 feet above the Ohio

River. The canal would need to climb over this ridge.

To move vertically, 107 locks were built along the length

of the Miami & Erie Canal, with 54 climbing from Toledo to the

Loramie Summit, and 53 descending to the Ohio River. A lock

(specifically a pound lock) is a chamber made of stone or wood with the

ability to raise or lower a boat to a different elevation. In the

case of the Miami & Erie, they were built 15 feet wide by 90 feet

long with tall retaining walls on each side. There were wooden gates at the ends that when closed formed a

“V” shape pointed upstream which used the the weight of the water above to hold the

gate closed. A canal boat would approach a lock and then call the

attention of the lock tender. The tender would assist with tie

ropes and operating the gates, as well as collecting tolls. If the

first gate was closed, they’d have to wait for the lock to be drained

or filled before proceeding. Otherwise, the boat would enter the

lock, and the gate it passed through would be closed. Operating a

gate could only be done when the water level was completely equal on

both sides, at which point the gate could be moved with a long pivot arm

extending over the bank. After the gate was closed and the boat

secured in place, a sluice gate (often referred to as a paddle) either

in the lock gate itself or underground, would be opened via a crank to

allow water to flow in or out depending on whether the boat was going up

or down. When the water reached the new level, the exit gate would be

opened and the boat could proceed. This whole process took about

10 minutes.

Using a lock drained a significant amount of water out of the upstream

length of the canal, so there were often wider pools to create extra

water volume and also give canal boats a place to wait if there was a

boat coming in the opposite direction. When the locks were closed,

water from above would either spill over the gates, or in the case of

the Miami & Erie Canal, a bypass channel was built on the heelpath

side so excess water could flow around the lock and then over a spillway

to the lower section of canal. All of the locks were built of cut

stone with wooden floors, although the 36 locks north of the Loramie

Summit to Defiance were built of wood. Some of those wooden locks were replaced with

poured concrete at a later date. Other locks, called guard locks,

were simply water control structures where water was fed from natural

streams into the canal. They could be opened, closed, or adjusted

to prevent excess water from entering the canal during floods, or to

increase water flow during dry times.

All this water had to come from somewhere, so natural and man-made

lakes,

reservoirs, and rivers were used to provide a constant supply of

water. One of the more challenging problems was supplying water to

the Loramie Summit, since no sizable lakes or rivers exist nearby at

that elevation. The Loramie Reservoir (Lake Loramie) was built in

1844-1845 to supply water to the summit, but this proved to be

inadequate, presumably because the flight of six locks at Lockington

drained a lot of water out of this section of canal. To remedy

this, an existing lake fed by small creeks and springs in Logan County

between Wapakoneta and Bellfontaine was was greatly enlarged in 1851 to

become the Lewistown Reservoir (Indian Lake). It provided a

consistent flow of water into the Great Miami River. Downstream, a

dam was built just east of Port Jefferson to divert water into the

Sidney Feeder Canal, which paralleled the west bank of the river through

Sidney to Lockington. The Sidney Feeder was also navigable and it

functioned as a branch line. The Mercer County Reservoir (Grand

Lake St. Marys) was constructed between St. Marys and Celina in 1837 to

provide water to the canal north of the Loramie Summit. Although

fairly shallow, it was the largest man-made lake in the world when it

was

built. A 2.5 mile navigable feeder connected the east bank of the

lake with the canal, and it allowed boats to traverse the lake to reach

Celina.

Beyond the summit, water could be fed by larger rivers such as the

Maumee, Auglaize, Mad, and Great Miami. At the lower end of the

canal in Butler and Hamilton counties, numerous small creeks in

Fairfield and West Chester were fed directly into the canal, as well as

some small spring-fed streams around Clifton in Cincinnati.

However, the only significant source of water to this lower 43 miles of

the canal came from the Great Miami River north of

Middletown where a large dam was constructed. This may explain why it took so long for the

water to reach downtown Cincinnati after the canal opened.

Although the canal paralleled Mill Creek for nearly its entire length,

it does not appear that the creek was ever used as a water source for

the canal, only as a means of draining overflow.

Early Operations

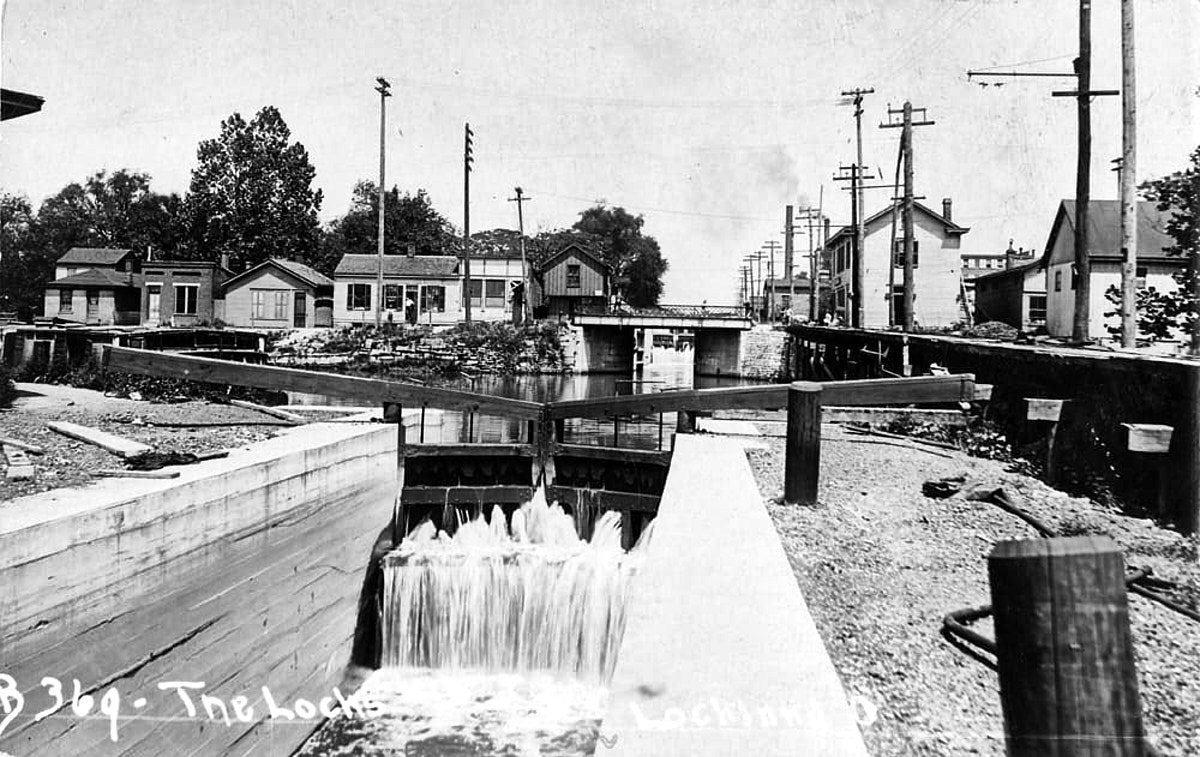

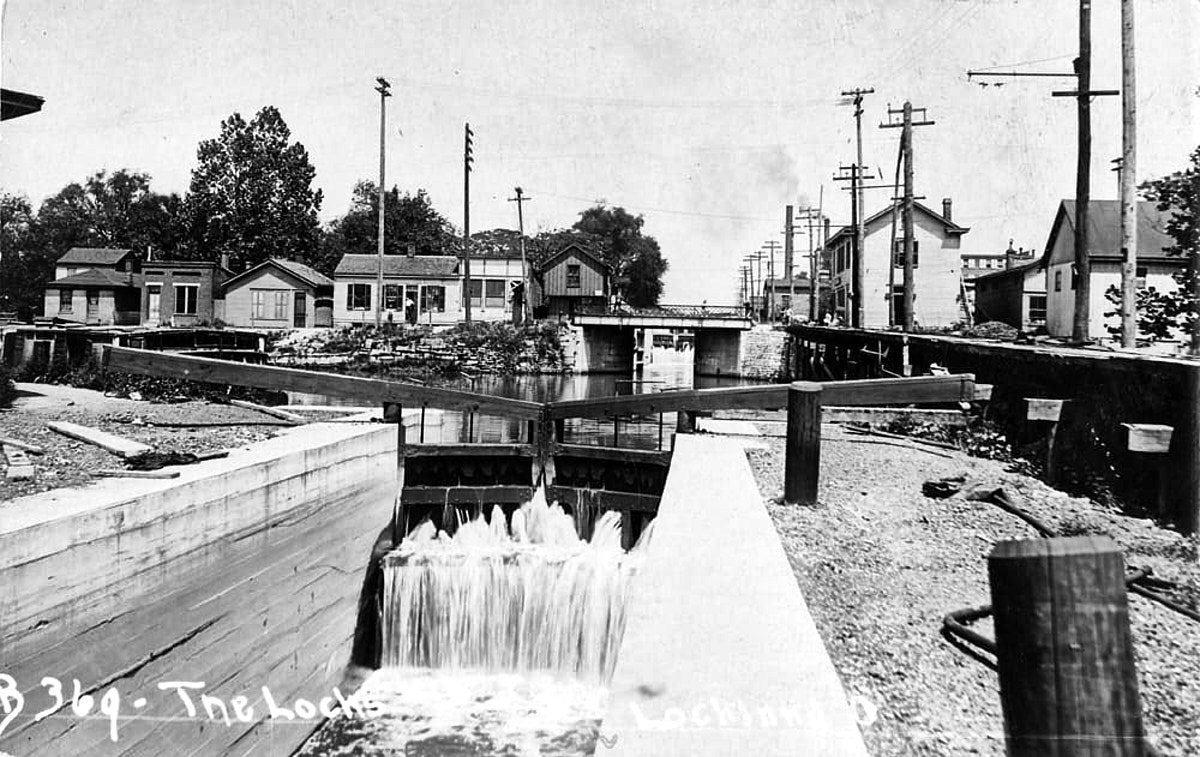

|

|

One of the four locks in Lockland that provided not only transportation but also water power to neighboring mills and factories.

|

After the canal became operational, villages and cities sprang

up along

its length to take advantage of the new transportation abilities.

Though primarily a freight-hauling operation, passenger transport was

popular as well for the first few decades. The canal also

became a valuable water power resource for mills and factories.

The state charged low rates for use of canal water as a way to encourage

industrial growth that would bring canal shipping and tolls. In

Cincinnati, the numerous breweries along the canal not only used it to

haul in their brewing feedstock and to distribute finished product,

they also made extensive use of canal water for cooling.

The potential energy of canal water is multiplied when there are

several locks in short succession, which was the case at Lockland. There were

three locks in a row between Wyoming Avenue and Patterson Street (Upper Lockland #40, Collector's #41, and Flour Mill #42). A

fourth one was located just a quarter mile downstream (Allen & James Service [?] #43). This attracted

numerous factories, and they built a complicated network of feed

channels, raceways, and basins to divert the water to their mills and

provide loading and unloading areas for canal boats. The most

notable was the Stearns & Foster Company, which was founded in 1846

to make cotton goods and upholstery for horse-drawn carriages,

eventually becoming a sizable mattress manufacturer. There were

other woolen mills, paper mills, blacksmiths, box factories, roofing manufacturers, and starch

processors in Lockland. Paper and grist mills set up at other

locks to the north of the city in Rialto and Crescentville to take

advantage of the water power. The cities of Hamilton, Middletown,

Franklin, Miamisburg, Tipp City, Troy, and Piqua all started as canal

mill towns with easy access to markets and adjacent productive

agricultural land. Lockington never developed much industry

however, perhaps due to the limited water availability at the summit,

but it did host a sawmill, grist mill, and grain silo. Purportedly

there were at least six saloons and a brothel in this small hamlet, set

up for weary travelers and canal boat crews awaiting the sometimes

hours-long trip through all six locks.

The goings were not always great however. Canal boats, often

family-owned where everyone lived onboard, would have to cease

operations in winter when the canal froze over. To take some

advantage of this limitation, numerous ice ponds were built adjacent to

the canal. They would fill their basins with canal water, and ice

would be harvested and stored in nearby ice houses until the

spring. When the canal thawed, ice would be sent to the cities via

canal boat. Even when freezing temperatures were not an issue,

problems with water flow or washouts caused by heavy rainstorms could

sever the connection between various sections of the waterway.

This made canals highly vulnerable to railroads that began opening up

even before construction was completed.

First Signs of Trouble

The canal was profitable at first, but revenues started to decline as

early as 1852. Railroads were opening throughout the state

in the 1840s, and they expanded rapidly in the 1850s. They had the

advantage of much quicker travel, especially important for passengers,

the ability to haul much more bulk in a single train, and they weren’t

strangled by freezing temperatures or a lack of rainfall. By the

1860s, the canal was only economically viable for shipping bulk

agricultural products, building materials, and other non-perishable

goods. Additionally, the sparse population and lack of industrial

development north of Dayton further limited the canal’s success.

Though the Great Black Swamp was gradually drained and it became highly

productive agricultural land, it still remained sparsely settled and

difficult to travel through during the canal era. It wasn't until

railroads were built through that area that development started to take

off.

The Warren County Canal was also having problems at this time. Due

to the persistent leaking of the canal, Shaker Creek was diverted into

it to provide extra water. This stream drained the large

swamp on the Shaker settlement at Union Village. It frequently

jumped its banks and flooded the canal, depositing sediment that

required constant dredging and repairs. Finally, Shaker Creek broke

through the canal's embankment in 1848. In 1852, John W. Erwin,

the resident engineer of the Miami & Erie Canal, investigated

repairs to the canal by direction of the General Assembly. Because

the canal had been little used, the State declined to repair it. In the

General Assembly, Representative Durbin Ward of Lebanon introduced

legislation to abandon the "Lebanon Ditch." In 1854, the state sold the

remnants for $40,000 to John W. Corwin and R.H. Henderson. The

large stones from the locks were sold off and used in local buildings

and bridges. The Whitewater Canal also suffered several disastrous

floods in 1847 and 1852, and it was finally abandoned in 1856 along

with the Cincinnati & Whitewater Canal. Parts of the

Whitewater Canal were retained for hydraulic water power use, but

railroads were quickly built over the towpaths and canal beds.

In 1861, the canal system was leased to a private operator for an annual

fee of $20,000 over a ten-year period. The operator soon discovered

that the canal in Cincinnati between the Lockport Basin at Sycamore

Street and its endpoint at the Ohio River was a liability. The

flight of ten locks, at which there was purportedly a toll collector at every single

one, was both too expensive and took too long to navigate. Since

Cincinnati itself had become a major market for the goods floating down

the canal, trans-loading canal barges to riverboats was less

necessary. Even for goods that did need to go to the river, it was

still cheaper to offload to wagons at the Lockport Basin for hauling to

the riverfront. Thus, in 1863 this last mile of the canal

was abandoned. The State of Ohio granted the city use of the canal

right-of-way to build a road, and the city spent a large sum of money

burying the old locks, grading Eggleston Avenue, and building a sewer to

maintain water flow from the end of the canal to the river. The

city then granted the Little Miami Railroad permission to build a track

up Eggleston that would eventually connect it with the Cincinnati,

Lebanon & Northern Railway terminal at Court Street. The Ohio

Supreme Court determined that this violated the agreement the state made

with the city, and Eggleston was forfeited back to the state.

This was advantageous for the railroad, since not long after this time

the city tried to eliminate railroads from city streets because they

blocked pedestrians and vehicles. Since the state owned the

street, the city had no authority to block railroad operations.

Decline & Failure

In 1871, the state renewed the lease with the investment company, but

declining revenues led to them relinquishing control in 1877, and the

state Board of Public Works resumed operations. The Miami &

Erie Canal Association was established in 1878 with the aim of

revitalizing the canal. They advocated for the construction of new canal

boats and improvements in the canal’s infrastructure, including larger

locks. Some of these upgrades were gradually implemented between 1904

and 1911. The association also backed the Miami & Erie

Transportation Company’s endeavor to lay tracks and utilize an electric mule to tow canal boats. This would replace animals

with an electrified railroad powered by overhead wiring similar to a

streetcar or electric interurban railway.

Plans for the mule to

run the full length of the canal were scaled back to just Cincinnati to

Dayton, and then scaled back again to Cincinnati to Hamilton.

Standard gauge tracks were laid on the towpath, and the electric mule

was put in service in approximately 1902 after an expenditure of roughly

$2 million. Steeple-cab three-phase locomotives were used to pull

the barges, but problems soon became apparent. At speeds any

greater than the three to four miles an hour usually achieved by horses

and non-electric mules, the boats would create so much wake that it

would wash out the canal bank. Faster speeds would also cause

boats to drag their keel on the bottom of the canal. The inertia

of a fully-laden canal boat was even enough derail the locomotive when

stopping abruptly. By 1905 the mule project was shut down and

scrapped.

|

|

Canal boats near Music Hall in

Over-the-Rhine are frozen in place and may be abandoned as the canal

falls out of use. The electric mule tracks on the towpath to the

left are already disused as well.

|

The work of the Association to upgrade the canal failed to

attract new

business and it fell into disuse. The last canal boat ran to

Sidney up the feeder canal in 1904 or 1905. The last boat on the

main canal in west central Ohio was piloted by Captain Billy Coombs. He

made the final run from a gravel pit outside of Newport to Ft. Loramie

in 1912. A canal boat operated by Captain Harry Newton crashed

into the aqueduct carrying the canal over Loramie Creek that same year,

severely damaging it. State officials refused to repair it. After this

time, canal boats were abandoned where they sat, often becoming derelict

platforms for neighborhood boys to fish from.

Though the canal was falling out of use for transportation, its value as

a source of water for industrial use remained. As the Cincinnati

neighborhoods and cities in the Mill Creek Valley industrialized in the

late 19th and early 20th centuries, the canal became a reliable source

of clean water that was used for various industrial processes then

dumped into Mill Creek. While an account of the Mill Creek in 1878

described it as clear with a pebbly bottom, by the first decade of the

20th century it had become a putrid mess of industrial and human waste

and it was one of the most polluted streams in the whole country.

Paper mills discharged spent bleach and hydrochloric acid, cotton mills

discharged caustic soda, and roofing manufacturers fouled

the water with asphalt and coal tar wastes. In 1910 the Ohio Board

of Health urged the state Board of Public Works to divert the canal’s

entire Sunday flow into the Mill Creek at Lockland to flush away the

industrial pollutants and sewage. The sizable overflow spillway

opposite Spring Grove Cemetery, as well as increasingly leaky aqueducts

in Carthage and at Mitchell Avenue, added much needed volume of clean

water to Mill Creek. Of the roughly 84 million gallons of water

brought into the Mill Creek Valley by the canal, only 48 million gallons

were discharged into the Ohio River. The remaining 36 million

gallons found its way into Mill Creek through various spillways, mill

races, percolation, aqueduct leaks, and factories. This increased

flow in the Mill Creek by some 35%.

The canal south of Dayton, which ran parallel to the Great Miami River,

was heavily damaged by the Great Dayton Flood of March 1913. After

a winter of record snowfall, heavy spring rains caused a massive flash

flood which inundated the Great Miami River Valley. This not only

destroyed every bridge over the river between Dayton and the Ohio

River, it also flooded the canal, destroyed aqueducts, washed out

banks, and damaged locks and culverts. The multi-span aqueduct

over the Mad River in Dayton was destroyed and it was never

replaced. The remaining segments of the canal elsewhere were

neglected and gradually deteriorated. This same storm damaged the

Ohio & Erie Canal, the southern portion of which was already

abandoned by 1911, and it wasn’t repaired either.

As more and more water was diverted out of the canal and into Mill

Creek, and as the canal further fell out of use, it became something of a

point of embarrassment to the city of Cincinnati. Since it ran

through the most urbanized part of the city, it became a dumping ground

for garbage and debris. Lackluster water flow would cause

stagnation and odor that was perceived as a public health threat, even

though the miasma theory of bad air causing diseases had been superseded

by germ theory in the late 1800s. The canal was rather unfairly

maligned in this respect, but it was used as a rallying cry to replace

the canal through the central city with a more modern transportation

system.

The Cincinnati Subway

In the first decade of the 20th century, proposals were being floated

for a new union station for the city’s railroads. Individual stations were scattered around the periphery

of downtown, which made connecting trips and freight interchange

excessively difficult. Several electric interurban railways

opened at this time as well, linking the city and rural communities with cheaper

and more frequent service than the steam railroads. However, they

either terminated near the edge of the city limits, or they had to run

lengthy and slow routes over the street railway system to reach

downtown. A solution was needed for both situations. The

railroad terminal studies, as well as the interurban connection

proposals, largely ignored the canal as a potential route.

Proponents feared that any rail proposal utilizing the canal would

invite public backlash due to the situation at Eggleston Avenue.

Since that section of the canal closed in 1863, it became a tangle of

railroad tracks with numerous sidings and spurs into the adjoining

factories and warehouses. Travel was excessively difficult through

that area due to trains frequently blocking the street. The

Gilbert Avenue Viaduct was built specifically to bridge this mess.

There was a real fear that this could happen along the whole rest of

the canal bed if it was converted to rail use. However, a

Parisian-style boulevard with a subway underneath was a more palatable

image for the city looking to improve its dirty industrial image.

The state agreed in 1911 to lease the canal lands to Cincinnati,

including for use as a subway, though restrictions on steam trains were

written into the agreement, limiting it as a freight or long-distance

passenger train system in favor of electrified rapid transit. The

lease itself was signed in 1912, and the city formed the Interurban

Rapid Transit Commission to begin planning.

|

|

Construction of the subway in the

canal bed. Note the lack of any underground utilities.

Digging was nearly as simple as if in a cornfield.

|

While the steam railroads looked to a riverfront or West End

location, and they eventually settled on the West End site that would

later become Union Terminal, Bion J. Arnold, the country’s preeminent

electric railroad

consultant, was hired by private business firms to develop a plan for an

interurban terminal system. He proposed a downtown loop under

Plum,

4th, and Sycamore, while the primary terminal and connection to the rest

of the rapid transit route would be under the newly-constructed Central

Parkway in the old

canal bed. The canal was a perfect place for a subway because few

or no utilities ran underneath it, making the excavation simple and

inexpensive. A much larger loop would follow the canal north to

St. Bernard where it would veer east through Norwood to Oakley, Hyde

Park, and O’Bryonville before following the slopes of the north bank of

the Ohio River to a tunnel under Mt. Adams and back to downtown.

The broad gauge interurbans that operated over the street railway would

be converted to standard gauge, since dual-gauge trackage in the subway

would increase cost and operational complexity. Of the nine interurban

lines serving Cincinnati, four were within easy reach of the proposed

loop, these were the Ohio Electric (precursor to the Cincinnati &

Lake Erie), the Cincinnati & Hamilton (Mill Creek Valley Line), the

Interurban Railway & Terminal's Rapid Railway division, and the

Cincinnati & Columbus. Due to the north and easterly route of the

loop, the Cincinnati, Lawrenceburg & Aurora was pretty much out of

luck, operating along the Ohio River to the west. The Cincinnati,

Milford & Blanchester planned to build an extension from their

terminus at Erie Avenue near Red Bank to the loop in Oakley via

Brotherton Road. The two IR&T divisions and the Cincinnati,

Georgetown & Portsmouth which operated to the east and terminated in

Columbia-Tusculum also were far removed from the loop. A proposed

concrete or steel viaduct to connect them to the loop near Torrence

Parkway was far too expensive for either company to handle, and they

were basically out of luck as well.

Since the Arnold report envisioned the loop to be entirely for

collecting interurbans that had no hope of supporting such an ambitious

project, in 1914 the city funded the Edwards-Baldwin Report. This

analysis eliminated some of the more extravagant connections to

far-flung interurban tracks and focused more on the logistics of an

urban rapid transit system. This report modeled the system on

Boston’s Cambridge-Dorchester subway (today’s red line) which could

achieve speeds of 45mph with grades up to 2%. This was first and

foremost a rapid transit system that could also operate mixed with

interurban trains. Thus, exclusive rapid transit vehicles and/or

electric streetcars would provide a backbone of service through the

system. As in cities like New York, Boston, and Chicago, it was

hoped that easier transportation to outer neighborhoods would allow

people to move out of overcrowded tenement buildings. The density

of Cincinnati’s Over-the-Rhine and West End neighborhoods was surpassed

only by New York, so there was pressure to provide transportation to

other parts of the city. The overall loop route from the Arnold Report

was retained, but Edwards-Baldwin made tweaks to alignments, surface

versus buried construction, and specific station locations.

The plan for the downtown loop was a variable that saw several proposed

options. One was similar to Arnold’s, another eliminated the

downtown loop by running the main loop under 9th Street and not

utilizing the canal until Plum, and a third kept the downtown loop but

eliminated the Mt. Adams tunnel for a more circuitous routing around the

hillside to Pearl Street. Even with such extravagancies as the

Mt. Adams tunnel and Columbia Avenue viaduct, the cost per mile was the

lowest of any subway project in the United States at the

time.

City voters overwhelmingly approved the issuance of $6 million worth of

bonds to finance construction in 1916. The city then immediately

started negotiations with the Cincinnati Street Railway to operate

it. Although the city had the authority to run the subway, this

was an opportunity to renegotiate the city’s franchise agreement with

the street railway company and to offload some of the cost of outfitting

the system to them. The street railway would purchase the cars

and all the electrical delivery components of the system, including

building a power plant. This would amount to roughly $2 million

above and beyond the cost of the infrastructure being handled by the

city. There was much contention between the interurbans and the

city over this agreement. Many of the interurbans that were built

to broad gauge so they could operate on the street railway were squeezed

out by incredibly expensive lease terms and restrictions, and they

feared the same fate in the subway with the Cincinnati Street Railway

running it.

|

|

What remains of the Race Street

subway station today. The through tracks are on either side, and

this stub-end track in the middle was for terminating interurban cars.

|

Unfortunately, just as the lease terms and operating agreements were

being formalized, the United States entered World War I. This was the

downfall of the project, since significant inflation left the bonds far

short of sufficient to build the proposed loop. Ratification of

the 18th Amendment and the start of Prohibition in 1919 also put a lot

of Cincinnati’s residents who worked in its breweries out of the job.

The reduction in tax revenues put further strain on building programs

like the subway. Two big changes were made to the loop proposal in

light of the reduced purchasing power of the bond money: both loops

were eliminated. The downtown loop, which was not part of the

canal and would require relocating numerous underground utilities, was

scrapped in favor of a terminal at Central Parkway. Also, only the

west leg of the overall loop would be built from downtown to St.

Bernard and east to a new proposed terminal in Oakley. The rest of

the loop coming back towards downtown through Hyde Park, O’Bryonville,

and Mt. Adams would be a later phase of the project.

After the lower end of the canal was abandoned for construction of the

subway, the entirety of the canal’s water was diverted over the Spring

Grove spillway on July 1, 1919, greatly improving water quality in the

most polluted lower part of Mill Creek. Not long after that,

subway construction began in the drained canal bed in 1920. Much

like the canal before it, sections were put out for bid by various

construction companies. All told, eight sections were built from

Walnut Street along Central Parkway and I-75 to the Norwood Lateral

Highway and Waterworks Park, though the final ninth section in

Oakley was never started. Money ran out before tracks, rolling stock,

or station fittings could be purchased, and by the time construction

ended in 1925, most of the interurbans were already out of business as

well.

At this same time, the old George “Boss” Cox political machine that had

been running city politics since the 1880s faced funding shortfalls

after decades of grifting and patronage. Murray Seasongood and the

Charterite party took control after extensive anti-corruption

campaigning. Seasongood then quickly removed appointees from the

prior administration, including those of the Rapid Transit

Commission. In 1927 he authorized the Beeler Report to study what

to do with the subway that had all tunnels, grading, and station

buildings completed to Norwood, though lacking any tracks, rolling

stock, electrical systems, or station appointments (they were basically

concrete shells). This report suggested some outlandish items like not

using the Liberty Street Station, demolishing others, and relocating

some of the right-of-way. This report seemed designed specifically

to sow confusion and consternation among the populace so they wouldn’t

support any further bond issues for completing the project.

A second and much more reasonable report in 1929 by Beeler proposed

using the extant subway from Northside to downtown for streetcars and

the Cincinnati & Lake Erie interurban. It nearly came to

fruition if not for the Great Depression. Also, the most difficult

and expensive section of the subway under Walnut Street to Fountain

Square and back would require several years of construction and

disruption to the city’s streets. This would overlap an election

season and potentially threaten Seasongood’s newly-held position of

power. So the subway was quietly let go as a failed project of the

previous administration. Cincinnati Mayor John Cranley would

attempt to kill the current downtown and Over-the-Rhine streetcar loop

in 2013 in a similar manner, though he was narrowly outvoted by the city

council. While the tunnels under Central Parkway remain to this day,

maintained in good condition, and still suitable for future light or

heavy rail plans, the critical and most difficult section of subway

under Walnut Street was never built. Most of the surface right-of-way

was obliterated by the construction of I-75 and the Norwood Lateral,

with only short unnoticeable stretches remaining. Some of the other

tunnels are still in place, but filled in or sealed up.

The End

|

|

A typical view of the remains of

the Miami & Erie Canal in rural areas. A drained channel that

is often overgrown and forgotten, but obvious to those who know what to

look for.

|

Just as the subway project fell dormant, a formal closing ceremony was

held for the Miami & Erie Canal in Middletown on November 2, 1929,

at the same site where ground was broken over a century earlier.

The water between Dayton and Cincinnati was shut off so highways could

be built on the canal right-of-way. Due to construction of the

subway, the transfer of water from the canal to Mill Creek had moved

upstream to Lockland in 1925 before being shut off entirely. With

the loss of the canal’s water, Mill Creek’s pollution problems would

become ever worse until interceptor sewers, treatment plants, and

environmental monitoring and regulation started to reverse the

tide. It still has a long way to go however.

Although Cincinnati’s subway never came to fruition, Central Parkway

did. Erie Boulevard in Hamilton, Verity Parkway in Middletown,

Riley Boulevard in Franklin, and Patterson Boulevard in Dayton are

similar roads built over the canal. The development around these

urban highways took on an automobile-centric pattern of parking lots,

service stations, large setbacks, and empty space. Such a built

environment is anathema to the transit-oriented development that would

have come with a subway, and the canal-era development that preceded it

has been whittled away by the entropy of modern planning. A

similar fate befell most of these narrow industrial canals that were

supplanted by railroads and highways. Waterways that can

accommodate ocean liners and similarly-sized barges have remained in

use, such as the Intracoastal Waterway, the Panama Canal, and the Ohio

and Mississippi Rivers, but even the enlarged Erie Canal in New York is

now mostly unused.

The history of both the Cincinnati subway and Central Parkway are

profound anticlimaxes that mirror the slow decline of the Miami &

Erie Canal on which they are built. The subway project is but a

footnote in history, and Central parkway was unceremoniously supplanted

by I-75. Much misinformation was spread about the subway from its

questionable public health impetus to urban legends about subway cars

not fitting in the tunnels or being able to make it around curves.

Even its route was dismissed by the Beeler Report and Seasongood as

being circuitous and inconvenient, despite running through the city’s

densest neighborhoods. Such misinformation and urban legends

persist to this day, and they pollute the discourse surrounding public

transit and alternative means of transportation. It’s rather

poignant that something as novel and historical as a canal would be

replaced by yet more roads and highways, which in the 21st century are

in no way novel and are actively destructive not only to the history

atop which they lie, but to the people and neighborhoods they ostensibly

serve. These early layers of history deserve to be remembered,

for they inform us about where we came from as a society, and where

we are going in the future.

What's Left

Cincinnati

In some places the Miami & Erie Canal is buried under multiple

subsequent layers of history, and just a short distance away it is

hiding in plain sight. Downtown Cincinnati has no visible remains

of the canal due to subway and Central Parkway construction

however. The locks under Eggleston Avenue could theoretically

still be buried under the street. The old Front Street bridge that

spanned the last reaches of the canal and its spillway does still

exist, but it is buried under Bicentennial Commons, with just a few sewer manholes to mark its location. Occasional air

vents, and bulkheads that block off old stairways to the subway, do

remain along the length of Central Parkway out to the Western Hills

Viaduct. These are most likely to be found in the median of the

parkway between Plum and Sycamore (Race street was the primary downtown

station), and at the stations at Liberty, Linn, and Brighton. Just

north of the Western Hills Viaduct the portals for the subway emerge

next to I-75. A little farther north are the south portals of the

short Hopple Street tunnel. The north Hopple portals were blocked

off and buried when the road was rerouted for I-75 in the 1960s.

Although Central Parkway follows the canal bed, the subway bypassed a

few sharp bends in the canal at Marshall, Bates, and Ludlow. I-75

sits atop the location of the Marshall bypass, where there was also a

station, but at Bates there’s a grade change and retaining wall behind

the Cincinnati Fleet Services building that marks the surface

right-of-way. There are no subway or canal remains at Ludlow due to the

highway, similarly along the hillside below Clifton. The Clifton

Avenue subway station wasn’t directly in the path of the highway, but it

was still demolished and regraded. Similarly, the overpass at

Mitchell Avenue, also the site of the canal’s first aqueduct north of

the Ohio River, was southeast of the highway, roughly where Comfort Inn

exists now, but it was all removed and regraded to build the exit

ramps. This aqueduct was originally a stone tunnel, which

collapsed in approximately 1890. A temporary wooden structure was

built until the final iron/steel aqueduct was built by the King Bridge

Company in 1897. The towpath bridge was upgraded to steel in 1902

to support the electric mule locomotives.

St. Bernard

|

|

An open area with subtle grading marks the path of the canal and subway in St. Bernard.

|

Just north of Mitchell along the north and west edge of St. Johns German

Catholic Cemetery, the canal and subway right-of-way emerge from under

I-75. The entrance to Ludlow Park and the lower part of Phillips

Avenue in St. Bernard are on the infilled canal. At Vine Street,

an old concrete retaining wall that currently holds up the hillside

behind Wiedemann’s Brewery was built to hold back the canal waters from

the lower area around Wiedemann’s. The hill above was filled in

over time to expand the parking lot opposite Washington Avenue for what used to be Chili Time. A

bridge carried Vine Street over the canal, which turned sharply north at

the location of the municipal building. The parking lot and

service road heading to the north northeast is still an open area

marking where the canal ran. There was a bridge over the canal at

Ross Avenue, but this has since been graded with earth. City Park

Drive follows the canal back to I-75.

Norwood

Beyond St. Bernard, the canal continued north while the subway route

diverged to the east to follow the Norwood Lateral, OH-562. The

highway is on top of the right-of-way until Reading Road, where

the subway grading then ran behind the former Showcase Cinemas property, now

the Mercy Health Home Office and Corinthian Baptist Church. A

shallow cut approached the intersection of Ross and Section Avenues

where a short tunnel was located to the B&O Railroad at today’s

Joseph Sanker Boulevard crossing. No portals remain and it’s

unclear if any of the tunnels remain. The subway then ran at grade

next to the B&O until Harris Avenue where there was another short

tunnel under the now-demolished Zumbiel Packaging factory. The

tunnel emerged at the baseball diamond in Waterworks Park just east of

Forest Avenue, also the terminal location of the Cincinnati &

Columbus Traction Company. The portals have been concreted over

and are mostly buried on the park side, though they’re still

visible.

Elmwood Place & Carthage

Back to the canal. From the I-75 and Norwood Lateral interchange,

the canal ran either under or somewhat to the west of the highway.

It dipped down away from the highway around Murray Road, following

Prosser Avenue and the end of Silver Street in Elmwood Place to Township

Avenue. The right-of-way is currently being used for electrical

transmission towers. At Poplar Street a few blocks further north,

the canal also came to the west and ran behind the apartment buildings

on Hasler Lane. There’s an old electrical substation building on

Spruce Street that has a sunken loading dock next to where the canal

once ran. The canal then crossed 66th Street before veering back

east to I-75.

Hartwell & Lockland

Where I-75 crosses Mill Creek, the canal had another aqueduct. It

then ran next to the Big Four Railroad through the area of the Ronald

Reagan Cross-County Highway OH-126 and Galbraith Road exits. There

appears to still be grading for the canal in this area, but it’s not

readily accessible. The canal ducked under the Big Four where I-75

southbound and Mill Creek cross. It followed the highway north,

but there was a sharper turn to the northeast

that the highway smoothed out. Muscogee Street near the Cincinnati

and Lockland border is at an odd angle that follows the old canal

route. There was also the first lock north of downtown at this

location, Allen & James Service (?) lock #43. Where I-75 crosses the West Fork Mill Creek the canal

crossed on an aqueduct. Then through the heart of Lockland were

the three locks in quick succession between Wyoming Avenue and Patterson

Street: Flour Mill lock #42, Collector's lock #41, and Upper Lockland lock #40. All of this was obliterated by the I-75 trench which is

something of an historical artifact in its own right by now, having been

built in the early 1940s. North of Lockland the highway is mostly on

top of the canal right-of-way.

Evendale & Sharonville

At Glendale-Milford Road I-75 and the canal part ways. Evendale

Drive veers off to the northeast while the highway continues due north.

To the left of Evendale Drive is what appears to be a large drainage

ditch, but it’s the canal mostly intact, though with little to no

water. It’s now used for drainage, and Evendale Drive sits on a

much widened towpath. Grading for business driveways and parking

lots removed any obvious semblance of the canal prism, but the ditch

itself is unmistakable. Near Sharon Road where Evendale Drive

splits off and Canal Road starts, the canal itself is filled in.

It took a quick S-curve through the neighborhood at the end of Woodward

Lane before picking back up parallel to I-75 west of the large UPS

distribution facility. The canal from here to north of Kemper Road

is intact and usually has some water in it, though it’s

overgrown.

Crescentville & Rialto

Despite proximity to the sizable I-75 and I-275 interchange, there are

still remnants of the Crescentville/Sharonville aqueduct over

a Mill Creek tributary behind Dubois Chemicals at the end of Champion

Way. Both abutments are there, though the north abutment is somewhat

buried under dirt and debris. The south abutment is completely

intact and old rebar is hanging out of the broken remains of the trough

that once spanned the creek. The Crescent Paper Mill lock #39,

which was near

Crescentville Road is gone. However, the Rialto/Friend & Fox

Paper Mill lock #38 remains about 200 feet south of the intersection of

Rialto Road and Port Union-Rialto Road. It is on private property

however. Between here and Hamilton there’s actually a surprising

amount of canal that’s still intact. Much of it has some water

flow, though not nearly to the depth it originally had. An

overflow spillway and creek culvert remains about 600 feet east of the

Ellis Lake Wetlands trailhead at Firebird Drive off of Union Centre

Boulevard. There’s a walking and biking path that parallels the

canal through here. Many of the lakes and ponds were formerly ice

ponds from the canal era. Other remnants of culverts, spillways,

and ice pond diverters may be found in this area.

Hamilton

Little, if anything, remains of the canal in the built-up area of

Hamilton. It came into town along Ramona Lane near the Butler

County Regional Airport, then it ran under today’s Erie Boulevard along

the east side of town. Since this was over a half mile from the

center of town, Hamilton financed the construction of their own basin

that ran between High Street and Maple Avenue (formerly Canal Street)

all the way to 3rd Street. Construction started in the spring of

1828 and the basin opened March 10, 1829. The basin was 148 feet

wide at the water line to permit the turning of canal boats. Eventually

it was lined with wharves serving shops and warehouses. By 1877

the basin had fallen out of use and it was filled in and replaced with

numerous railroad tracks, some of which remain today.

On the northeast side of Hamilton where Greenwood Avenue becomes Canal

Road, the canal itself starts to become visible to the east side of the

road. This rural area north of Hamilton represents a sandwich of

19th century infrastructure. The Ford Canal hydraulic is to the

west of Canal Road, which was opened on January 27, 1845 to provide

water power for mills at the north end of Hamilton near 3rd and Black

Streets. The water is diverted from the Great Miami River at a dam

about 3.5 miles upriver near Rentschler Forest MetroPark. The

hydraulic provides 29 feet of fall and it spurred industrial development

of the northern part of Hamilton. By the 1910s it was mostly out

of use as factories had switched to coal-fired steam power. Henry

Ford purchased the hydraulic in 1918 and restored operation to provide

electricity to a new tractor factory. In 1963 after changing hands

a few times, the hydraulic was purchased by the City of Hamilton who

still operates a two megawatt hydroelectric generator at their 3rd

Street power plant. On the opposite side of Canal Road is the

Great Miami River Recreational Trail on the Miami & Erie Canal

towpath. The canal prism itself is visible here though there’s

little or no water in it. On the heelpath side, generally a bit

farther uphill, was the CH&D Railroad’s East Middletown

Branch. That section of the branch line was made redundant in 1927

when the Woodsdale cutoff was built from a new yard on the CH&D

mainline at New Miami. The cutoff provided a direct connection

from the blast furnaces in New Miami to Armco Steel in Middletown, and

it avoided congested tracks and sharp curves in the middle of Hamilton.

The old branch route was formally abandoned in 1934 save for about a

mile in Hamilton to the county fairgrounds that continued serving online

industries until 1972.

Rentschler Forest

|

|

Remains of the Excello lock in the

present-day. Even though it was rebuilt in the first decade of the

20th century, it is still in rough shape.

|

Near where Canal Road does a two-point turn just west of Headgates Road

(named for the Ford Canal Hydraulic’s headgate/guard lock) there’s a

small stone structure in the canal bed that appears to be a water

management dam. There’s slots in the walls to allow wooden beams

to block the water flow, likely to serve ice ponds that were still in

use after the canal was abandoned. In Rentschler forest the canal

is plainly visible with some swampy plants in the bottom. Only

some broken concrete remains for a small culvert over Kennedy Creek just before it

flows into the Great Miami River. Next to it is a small

stone culvert under the park road (formerly the CH&D) and a larger

stone bridge for the walking path (a former roadway). Immediately

east of there is a small driveway and parking lot at the riverbank, and

there’s a sizable riprap overflow spillway for the canal. At the

east end of the park, Reigart Road sits on the heelpath and the old

railroad right-of-way. Where the road ends the recreational path

starts climbing up the hill away from the canal and railroad since the

Woodsdale cutoff comes in from across the Great Miami River shortly

thereafter.

Liberty Township & Excello

From this point north, the railroad continues to operate, mostly on the

heelpath of the canal. It’s rather inaccessible with few street

crossings. Concrete and stone rubble is all that's left of the

LeSourdsville/Gregory Creek aqueduct

in Monroe Bicentennial Commons (formerly LeSourdsville Lake Amusement

Park).

Approaching South Main Street in Excello, the canal and railroad part

ways to sandwich the property of the old Harding-Jones paper mill.

This mill operated from 1865 until 1990, and it was demolished in

2018. Newer flood walls behind the paper mill site mark the canal,

whereas the railroad runs through the front of the property. On

the other side of South Main Street is the Excello (or Excello Mills)

lock #34, which was the

first lock completed on the Miami & Erie Canal in 1826. The

lock itself is easily accessible and visible from the road, and the

spillway, where water was also diverted for use by Harding-Jones, was

cleared of brush and trees in early 2024 to make it more visible.

The lock was rebuilt with

concrete sometime between 1905 and 1911. A short distance away

there may be some remains of the aqueduct over Dick’s Creek near the

OH-4 and Oxford State Road exit, but that area is difficult to access

and the aqueduct was supposedly removed for road construction.

Just 300 feet north of OH-73, remains of the Amanda's Mill lock #33

forms part of the foundation for Cohen Recycling's Middletown facility

next to Verity Parkway.

Middletown

Verity Parkway marks the route of the canal through Middletown, except

for the four blocks between 2nd and Vail Avenues. Verity used to

run over the canal bed half a block to the west of today's Verity Parkway/Canal Road, but it was rerouted in the

mid-1970s as part of the City Centre Mart project. This was an

ill-fated downtown revitalization project that enclosed two blocks of

Central Avenue Broad Street to create a downtown

mall that retained many of the original buildings as tenant

spaces. Reconstruction of the streets and disruptions to traffic

flow put many of the already struggling stores out of business.

Verity Parkway was removed from the old canal bed and northbound traffic

was diverted to Clinton Street while southbound traffic was diverted to

Canal Street, eliminating a couple of very small oddly shaped

blocks. After high vacancy and increasing maintenance expense, the

mall's hallway structure was demolished, and the street grid was

restored in 2001/2002. The parking garage was demolished in

2010/2011. South of Reynolds Avenue is the Middletown Transit

Station, which sits in a large parking lot whose land was cleared for an

anchor store and additional parking garage that were never

built. The transit station sits at the former meeting point of the Miami & Erie Canal and the Warren County

Canal.

A small

canal memorial exists north of Central Avenue with historical

information and a fountain made to look like the canal with lock

gates. At the north side of town is the canal museum at Verity

Parkway and Tytus Avenue. The Middletown Hydraulic Canal sits on

the west side of Verity Parkway at that location as well. This was similar to the Ford

Canal in Hamilton and it was used exclusively for water power.

It's mostly intact but empty. The

two canals part ways at Hughes Street, but they come back together at

Access Road between Lowell and Bryant Streets. This was a busy

location where a feeder from the Great Miami River supplied water to

both the Miami & Erie and the Middletown Hydraulic. The dam in

the river was demolished in 1993. Dine’s lock #31 was also

located

here, buried by Verity Parkway, but the headgate structure for both

canals remains to the north of the road. The old feeder for the

Warren County Canal came off of

the next lock just a few hundred feet to the northeast along Tytus

Avenue, Lower Greenland lock #30, since the Warren

County Canal was 16 feet higher than the Miami & Erie with two locks

at downtown Middletown. There appears to be remnants of the Lower

Greenland lock buried in the front yard of the ODOT and Ohio BMV

facility at Tytus and Hawthorne. The canal ran along Tytus east of

Lowell, whereas Verity follows an alignment of the Ohio Electric/Cincinnati & Lake Erie. Beyond Middletown, Verity Parkway/OH-73 is

essentially over top of the canal.

Franklin

On approach to Franklin, the canal deviated from the highway to the

south to swing through the R Good Industries facility, formerly the

Franklin/Clutch's Paper Company, before curving

back towards Riley Boulevard. There are infilled remains of lock

#28, named Franklin/Clutch's Paper Mill,

just east of Dixie Highway. A few hundred feet to the north, a

shallow row of stones in the creek bed appears to be the only remains of

the triple-arch stone aqueduct over Clear Creek next to Riley

Boulevard. Through the rest of Franklin Riley is on the canal

bed. North of town where Riley merges

with Main Street, the canal remains to the east of the highway.

Franklin also had a separate hydraulic canal that came off the Great

Miami River opposite Chautauqua and opened in 1870. A sizable

headgate and concrete

channel remain at this location next to the recreational trail, and

much of the hydraulic is evident from Jackson Street and Atlas Roofing

to the headgate structure, though the hydraulic didn’t interface with

the Miami &

Erie. The Chautauqua Reservoir was drained when the dam was

removed in the 1980s or early 1990s. Just north of the dam

location near the south end of

Crains Run Nature Park is Sunfish lock #27 on the east side of

Dayton

Cincinnati Pike. It’s of similar concrete construction from the early 20th century as the

Excello lock. Two large culvert pipes took the

spillway water around the back side of the lock under an earlier

alignment of the Big Four Railroad.

Miamisburg

|

|

An impressive overpass and viaduct carries the former Big Four Railroad over the Miami & Erie Canal south of Miamisburg.

|

South of Miamisburg is an imposing truss bridge and viaduct that carries

the former Big Four Railroad (now Norfolk Southern) over the remains of

the canal and Dayton Cincinnati Pike. After the devastating flood

of 1913, the Big Four bypassed their old route through Franklin by way

of Carlisle and two bridges over the Great Miami River. Due to the

shallow angle at which the new elevated railroad bridge crosses the

highway and the former canal, a sizable two-span skewed Pratt

through-truss bridge was built to span the highway. A viaduct made

up of several plate girder spans with small trusses was also built to

carry the railroad over the canal, which is dry but still very

evident. In fact, from this point all the way north to Miamisburg

Community Park, the canal prism is entirely intact, just drained of

water and planted with manicured grass. At the park the trench

ends, but the right-of-way continues along the east side of 1st Street

and no buildings sit on top of it, just parking lots and lawns.

There are a couple of old canal-era buildings that sit on the

heelpath side of the canal between Laurel and Central Avenues.

At the municipal building the canal started to veer slightly to

the east. Keelboat Park on Pearl Street has an old wall and

railing that is likely a culvert from when the canal was no longer

navigable but still used to convey water. A few blocks north of

there, Canal Street points the way to the location of the Sycamore Creek

aqueduct, which may have some remains.

North of here, the canal reappears as a shallow ditch following the east

side of Main Street and later Dixie Avenue. The recreational

trail is on a later right-of-way of the Ohio Electric/Cincinnati &

Lake Erie interurban, which relocated off of the highway in 1908.

On approach to West Carrollton at Riverside Auto Parts, the recreational

trail turns north to follow the Miamisburg & Carrollton

Hydraulic. This hydraulic canal was built in 1867 from a dam on

the Great Miami River near Miami Bend Park to provide extra water to the

Miami & Erie for industrial use in Miamisburg, mostly for paper

mills. It was reorganized as the Miamisburg Hydraulic Company in

1874. When the Miami & Erie Canal fell out of use, the

hydraulic company obtained permission from the state in 1920 to block

off the abandoned Miami & Erie Canal immediately north of where the

hydraulic feeder entered the main canal. They maintained the rest

of the Miami & Erie Canal south of this point to the aqueduct at

Sycamore Creek in Miamisburg, where several factories were

located. Around 1926, The Ohio Paper Company acquired all

outstanding stock of the Miamisburg Hydraulic Company. R.P.

Munger, a representative of The Ohio Paper Company, acted as President

from 1933 through at least 1955. That year, the company agreed to sell

an easement for $1.00 to the Miami Conservancy District so they could

build a levee on the land. This was most likely the end of the

hydraulic and this section of the Miami & Erie, though it remained

on maps well into the 1980s.

West Carrollton & Moraine

The canal took a straight shot through the center of West Carrollton

along the south side of Central Avenue. Little, if anything,

remains. Marina Drive in Miami-Erie Canal Park marks the route,

though there isn’t anything notable to see here either due to road

realignments and construction of the I-75 Dixie Drive exit. The

canal does reappear as a ditch to the east of Dryden Road just past Main

Street in Moraine, though much of it has been filled in. North of

the I-75 Dryden Road exit, the canal followed Arbor Boulevard, but

there doesn’t seem to be anything remaining.

Dayton

After crossing I-75 yet again, the canal right-of-way picks up along the

hillside at the south side of Carillon Park. Smith's Distillery

lock #17, which was originally located in Huber Heights, was dismantled

and reconstructed in the park along with a lock

tender/superintendent’s house. The canal continued along

this hillside until nearly South Main Street, where it turned sharply

north towards downtown Dayton. Power lines mark the Ohio Electric

Railway route which was on the uphill heelpath side of the canal.

Construction of the athletic fields and other facilities surrounding the

University of Dayton have wiped away any trace of the canal south of

Apple Street. North of Apple Street, Patterson Boulevard is on the

canal. Between 3rd Street and 2nd street a shelf of land to the

east of Patterson marks the canal, and the land drops off several feet

to the east. Between 2nd and Monument there are shallow

reconstructed sections of canal on the east side of the street. At

Monument, the canal turned to the northeast to run along Water Street

and through barren industrial land towards the Mad River. The

south abutment of the Mad River aqueduct remains along the recreational

trail near the end of Ottawa Street. This aqueduct, which was a

wooden 3-hinged arch sitting on stone piers, similar to the Great Miami

River and Dry Fork Creek aqueducts on the Cincinnati & Whitewater

Canal, was destroyed in the 1913 flood, and only the ruins of the south

abutment remain.

Beyond Dayton

Generally speaking the canal continued to follow the east side of the

Great Miami River until I-70. There are some canal locks and small

parks marking points of interest. At the Taylorsville dam, the

canal crossed the river on a large aqueduct and embankment. The

earthworks remain, as does part of the aqueduct's western abutment. A recreational trail follows the canal most of

the way to Troy, with locks accessible nearby, especially in Tipp

City. North of Troy the canal was basically smashed between County

Road 25A and the Great Miami River. It ran through the middle of

Piqua between Main and Spring Streets where a large alley/parking area

marks the spot. Johnston Farm north of Piqua has a canal boat in a

short section of intact canal up to the next lock about a mile

upstream at Loramie Creek. Lockington is just another mile farther

north, where the five locks in a row remain (the aqueduct over the

Great Miami River and the sixth lock are out of reach). Some parts

of the Sydney feeder remain east of here as well.

Past Lockington the canal runs through open country, much of it with

at least some water in it. North of Fort Loramie it is actually

very evident with a fair amount of water flowing, just not at full

depth. It is completely intact and maintained through the

heart of Minster, though street crossings make it un-navigable.

Between Minster and New Bremen it is overgrown and stagnant, but mostly

full of water. New Bremen has intact and full sections, including a

restored lock. North of New Bremen the canal is treated as mainly