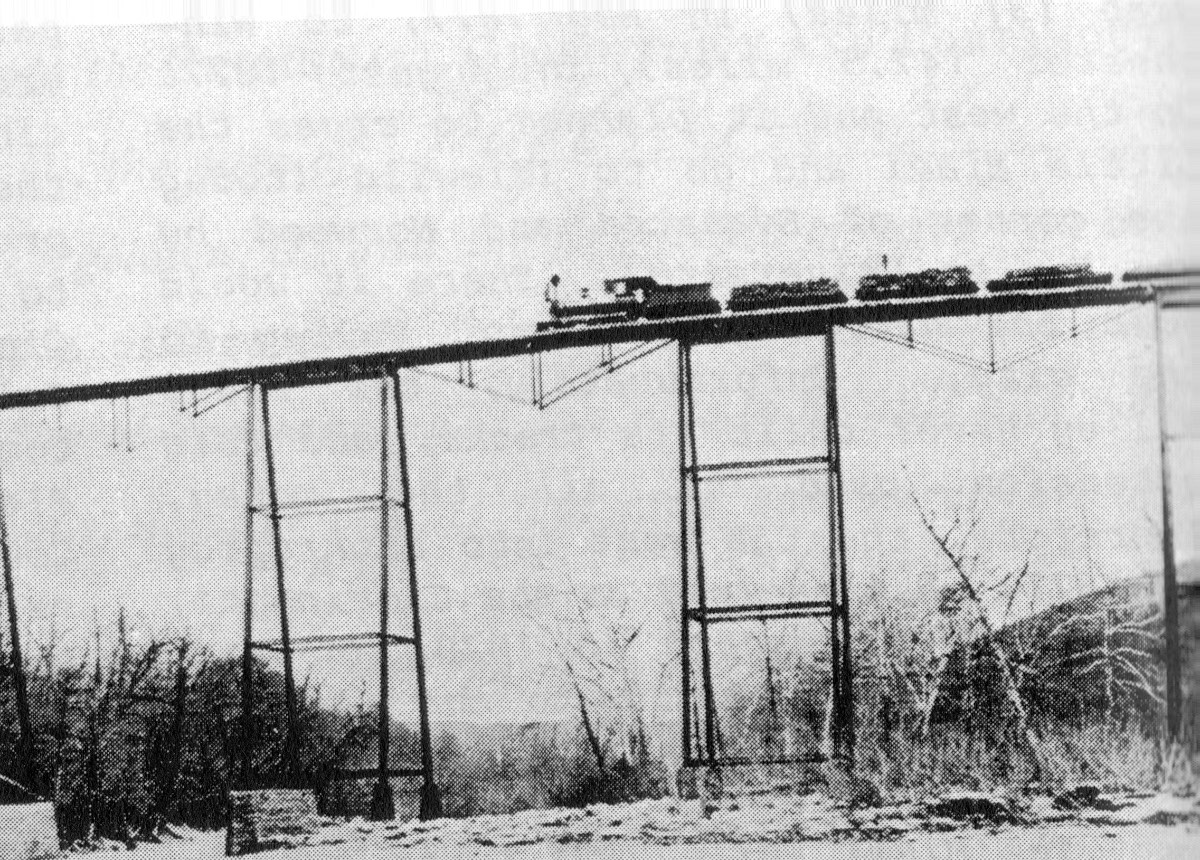

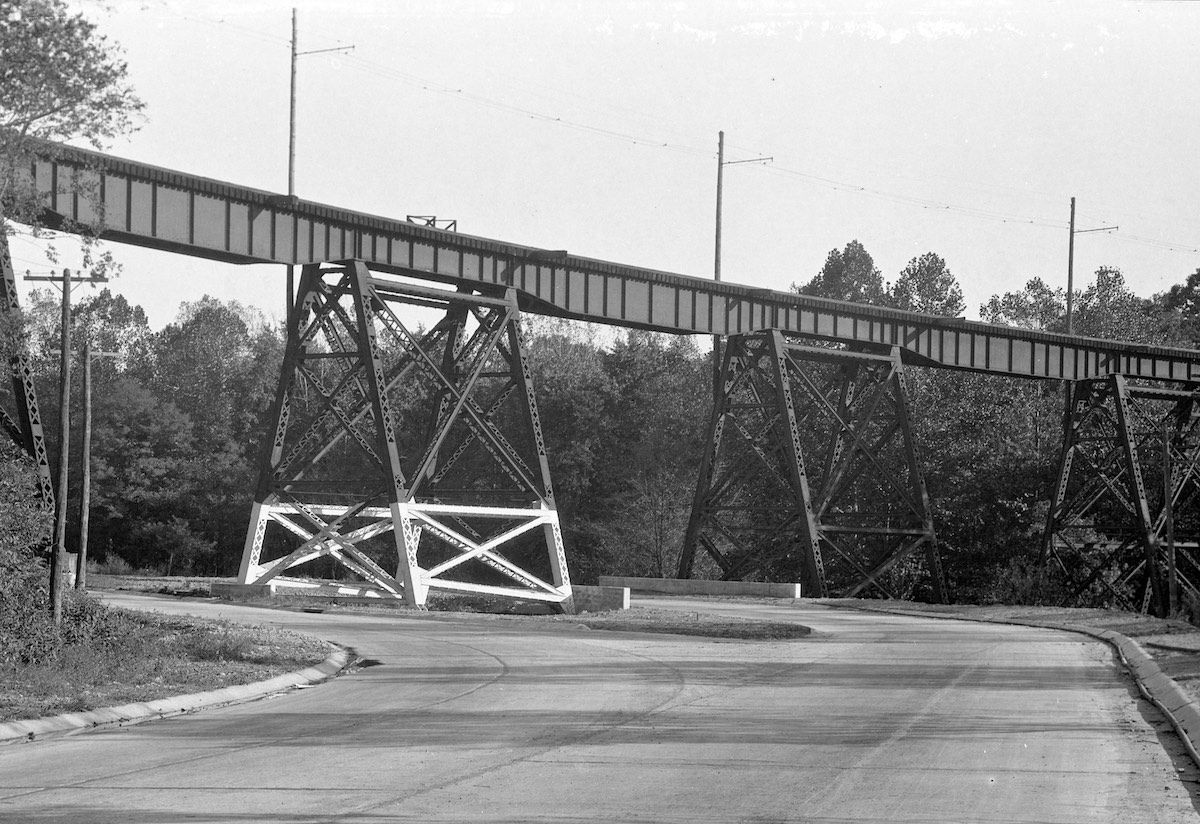

CG&P trestle over White Oak Creek west of Georgetown, shortly after completion. From "Railroad With Three Gauges" by David McNeil.

CG&P - Cincinnati, Georgetown & Portsmouth Railroad

Columbia - Georgetown, branches to California, Batavia, Russellville, and Felicity

1877-1936

Narrow gauge, steam line constructed by the Cincinnati & Portsmouth Railroad, 1876

Renamed the Cincinnati, Georgetown & Portsmouth Railroad, 1880

Construction to Georgetown completed, 1886

Dual (narrow and standard) gauge California waterworks branch built, 1899

Converted to Standard Gauge & Electrified, waterworks branch extended to Coney Island and broad gauge rail added,1902

Batavia branch completed, 1903

Russellville branch completed, 1905

Felicity & Bethel branch completed, 1906

Steam freight service ended, 1915

City service to downtown suspended, 1918

Reorganized as the Cincinnati-Georgetown Railroad Co., 1927

California branch abandoned east of the waterworks, 1927

Felicity & Bethel branch abandoned, 1933

Batavia and Russellville branches abandoned, 1934

Passenger service suspended, and all service abandoned east of Bethel, 1935

All service abandoned, remaining track between Carrel Street and the waterworks sold to the city, 1936

City/waterworks use suspended, 1943

|

CG&P trestle over White Oak Creek west of Georgetown, shortly after completion. From "Railroad With Three Gauges" by David McNeil. |

[Note there are many small mistakes in the following dates, refer to the years in the list above] This company completed a 3-foot-gauge steam railroad between Cincinnati and Georgetown (41 miles) in 1886, and in 1902 both converted it to standard gauge and electrified it. A branch from Lake Allyn to Batavia was opened at the same time. The company also operated a 5'-2 1/2" line to Coney Island that entered Cincinnati over the street railway. The standard-gauge line was extended from Georgetown to Russellville (8 miles) in 1904. An affiliate, the Felicity and Bethel Railroad (9 miles) was opened in 1906. The CG&P hoped to build east to Portsmouth, but although it did some grading between Russellville and West Union, it lacked the funds for completion. The road always retained much of the character of a shortline railroad, in spite of its electric operation. It interchanged railroad freight, operated a railway post office, and even interchanged a passenger car with a steam short-line, the Ohio River and Columbus Railway to serve Ripley, Ohio. the Felicity and Bethel used a steam locomotive for freight service.

The company failed in 1927 and was reorganized in 1928 as the Cincinnati Georgetown Railroad Company. The new corporation abandoned the Georgetown-Russellville extension in 1933, and in 1935 abandoned the outer 20 miles of the remaining main line, as well as the Batavia branch. It gave up passenger service at the same time. In 1936, it abandoned the rest of the property. (From: Hilton, George W. and John F. Due, The Electric Interurban Railways in America. Stanford University Press, 1960)

The Cincinnati, Georgetown & Portsmouth Railroad was one of the more unique interurban operations in Cincinnati, due to its narrow gauge history and complicated set of expansions, gauge change, and electrification in the early 20th century. The history is not unlike the Cincinnati & Lake Erie, which also had fairly meager beginnings as a narrow gauge steam railroad, but which grew into part of a larger system. The CG&P also served territory that had no other steam railroads, and although it wasn't nearly as strong as the lines north towards Dayton, it held its own well enough and almost became part of the large Pennsylvania Railroad empire.

Land acquisition began in 1873 and construction of the narrow gauge steam railroad started in 1876. The first train ran to Mt. Carmel in 1877 and Amelia in 1878, with grading finished to White Oak. By this time the money was exhausted, and the line was put into receivership and reorganized in 1880. Construction continued, and the line reached Bethel in 1881 before stalling again due to a further lack of funds and damage from floods on the long trestle across the Little Miami Valley. 1886 saw completion of the massive White Oak trestle and operations finally reached Georgetown. That same year, the Cincinnati & Eastern (later the Norfolk & Western "Peavine") reached Portsmouth, ending all discussion of continuing CG&P construction further east.

The Railroad With 3 Gauges (the name of David McNeil's book on this railroad) operated at one point narrow, standard and broad gauge rails all at once from their Carrel Street yards to California. As a narrow gauge steam railroad in its early life, it was similar in character to the Cincinnati & Westwood and the College Hill Railroad, with aspirations for expansion not unlike the nearby Norfolk & Western Peavine or the Cincinnati, Lebanon & Northern, both of which also began life as narrow gauge railroads. However, even after electrification and conversion to standard gauge, the CG&P maintained its status as a railroad, just an electrified one, which gave it some advantages with the Public Utilities Commission. They were also able to continue interchanging freight with the Little Miami/Pennsylvania Railroad, which was notoriously hostile to interurbans. Nevertheless, the CG&P considered itself an interurban when it was deemed convenient, and although it had its own private right-of-way for pretty much its entire length, the sharp turns, heavy grades, and frequent stops (although it at least had a fair number of actual station buildings, platforms, and shelters) made it much more like other interurbans than a steam railroad. Had a less torturous route been surveyed, likely bypassing Mt. Washington in favor of an easier climb to the hilltops, it's possible the CG&P could have become a feeder branch to the Little Miami/Pennsylvania. It had both a direct connection with that line at Carrel Street, and by the turn of the 20th century it was owned by Little Miami/Pennsylvania officials, though no actual corporate takeover or merger was ever initiated.

Little happened with the CG&P until the waning days of the 19th century. Like many small narrow gauge systems, the CG&P operated only a few trains per day, with three scheduled trains and probably one or two unscheduled freights. By this time however there was a lot of buzz about the new electric interurban lines being built all over the country, while at the same time the problems of narrow gauge operations were well known and all efforts were being made to convert narrow gauge systems to standard gauge. At this same time, Cincinnati was planning to build a new water treatment plant in California, and they needed a way to haul in construction materials. The branch to the California waterworks was built in 1899, with the city of Cincinnati handling construction of the Lick Run Trestle over Kellogg Avenue, which was then leased to the CG&P. This branch line was built with a dual gauge, and the main line had a third rail added back to Carrel Street so standard gauge freight cars from the Little Miami/Pennsylvania Railroad could be hauled to the waterworks with the CG&P's narrow gauge locomotives. Note that dual gauge track on the CG&P was set up with only three rails, with all cars sharing the left rail when heading east. This saved money since only three rails were needed instead of four (or four instead of six for a three gauge setup), but it also meant that using different gauge cars or locomotives in a single manifest required offset couplers since the centerlines of the different gauges didn't match up. In 1900 the CG&P purchased a second hand standard gauge switcher locomotive to handle these movements. After construction of the plant was completed, the CG&P continued to bring in chemicals and sometimes coal, while also establishing passenger service for California residents.

|

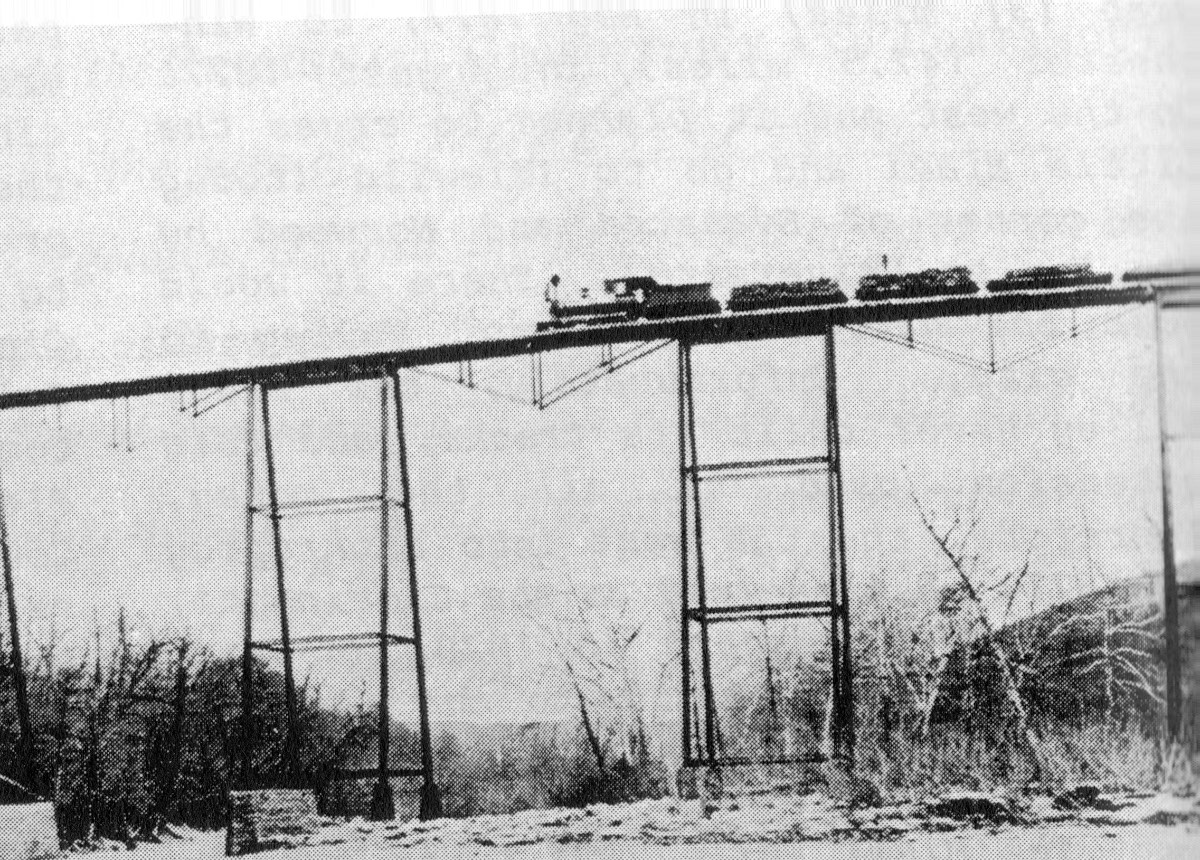

CG&P Carrel Street yard in 1902. A broad gauge city car is on the left track, while a tangle of narrow, standard, and broad gauge tracks interconnect on the right. From "Railroad With Three Gauges" by David McNeil. |

1902 was the year that the CG&P was both converted to standard gauge as well as electrified, making it one of the first steam railroads in the country to convert to electricity. The company also changed hands and a number of loans were taken out to finance the reconstruction and expansion of the property. During construction of the competing broad gauge Interurban Railway & Terminal lines which could operate all the way to downtown, there was a push to extend the CG&P from the waterworks to Coney Island to capture some of that business, which would be a lot easier with electric cars. This extension was done to match the street railway's and IR&T's broad gauge tracks. The first electric car to Coney Island ran on July 26, at which point there were narrow, standard, and broad gauge tracks between Carrel Street and the waterworks, with broad gauge tracks from the waterworks through California to Coney Island. The main line was still narrow gauge from California Junction out to Georgetown, but there was some dual gauge trackage as well, at least to Mt. Washington. The final changeover from narrow gauge steam to standard gauge electric cars on the mainline happened on December 1, 1902. So there was only a three month period when all three gauges were used concurrently. After the final changeover, all the narrow gauge equipment was either scrapped or converted to standard gauge. Most of the old coaches were turned into waiting shelters, while some of the freight cars got new standard gauge trucks. Although this marked the end of steam passenger operations, the company continued to use standard gauge steam locomotives for freight service. The broad gauge city cars were not able to go downtown until mid-February 1903 when the Cincinnati Traction Company built the connecting tracks on Carrel to Kellogg and to the new Donham Avenue viaduct they were constructing for use by the CG&P and the IR&T lines. This viaduct allowed the CG&P cars to Coney Island and the IR&T to cross over the Little Miami Railroad and connect directly with the East End streetcar line to get downtown.

A brief mention must also be made about the Ohio River & Columbus Railroad, whose life was tightly entwined with that of the CG&P. As mentioned in the Norfolk & Western Peavine history, there were plans in the 1870s for the Columbus & Maysville to build a line between its namesake cities via Washington Courthouse, Hillsboro, Sardinia, Georgetown, Ripley, and Aberdeen. Only the leg between Hillsboro and Sardinia was completed however, in 1879, and it became the N&W Hillsboro branch after the usual mergers and acquisitions. The OR&C, an independent entity from the C&M, N&W, or CG&P, opened a standard gauge steam road between Sardinia and Ripley in 1903, presumably on the same route the C&M had proposed. Connections were made with the N&W at Sardinia, the CG&P at Georgetown, and riverboats at Ripley. However, extension to Aberdeen and electrification was never accomplished because of financial hardships. Due to the central connection at Georgetown with the CG&P, and more favorable freight handling rates than the N&W, the two railroads became rather dependent on one another. Nonetheless, there was an excessive amount of bickering over facilities in Georgetown, freight car charges, and other petty squabbles. With lousy connections to other railroads and a sparsely populated tributary area, the OR&C was abandoned in 1917. An accounting of the freight revenues for the line led CG&P officers to conclude it wasn't worth taking over and turning into an electric branch line.

Electrification was intended to breathe new life into the CG&P even with no more prospects for connecting to Portsmouth. A series of branches were opened to Batavia and Russellville in 1903 and 1905 respectively. Grading was reportedly completed east of Russellville to West Union, though funds were never available to lay track. Aerial photographs and topographic maps suggest that the West Union grading only made it as far as Eagle Creek, about three miles southeast of Russellville. The Felicity & Bethel, technically a separate entity, though functionally just another branch line, also opened in 1906. Even though revenues nearly doubled between the late 1890s and early 1900s, the CG&P and its various officers spent the next three decades trying to pay back the debt on the electrification, gauge change, and construction of the branch lines. This was a perpetual sore point, but considering the lousy grades, and other operational constraints that don't lend themselves well to steam operation, the money was probably well spent in the grand scheme of things.

|

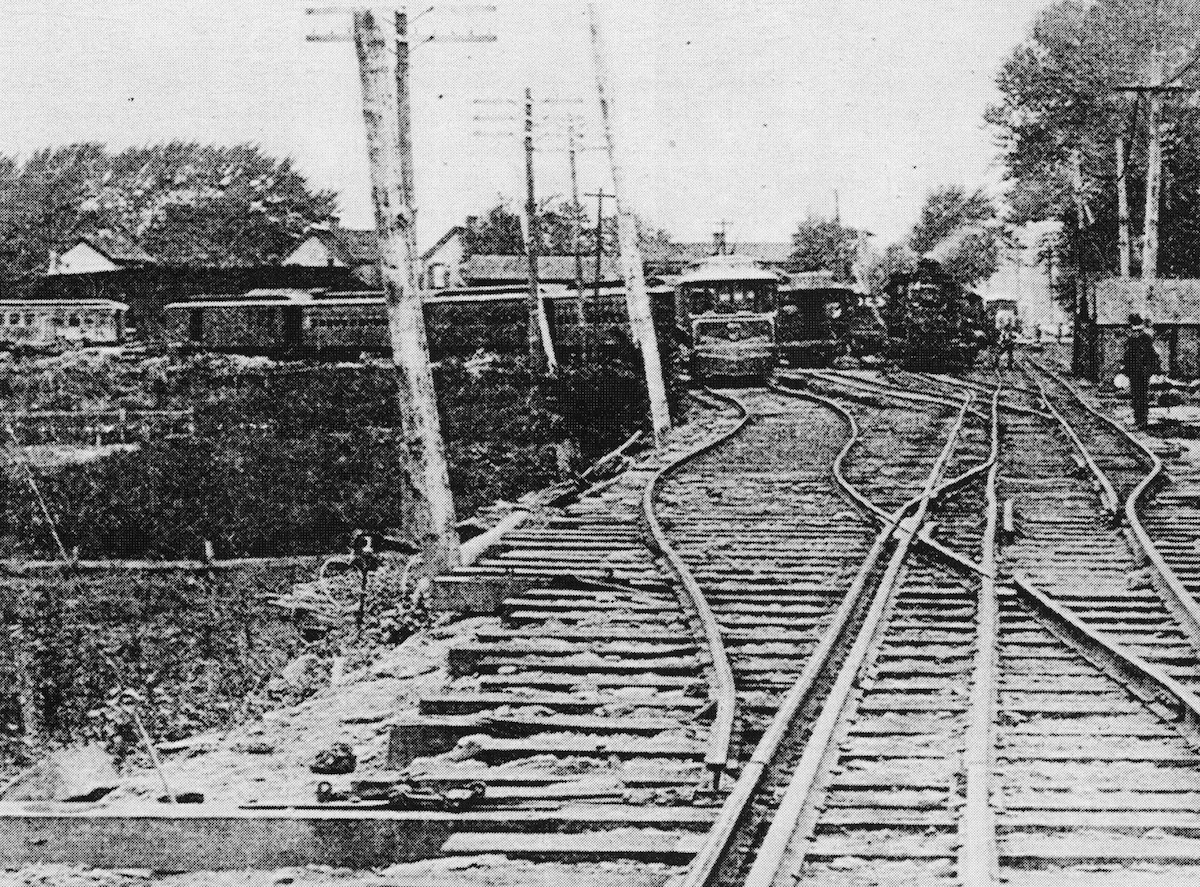

Donham Avenue Viaduct over the Pennsylvania/Little Miami Railroad. From "The Pennsylvania Railroad in Cincinnati" by Rick Tipton and Chuck Blardone. |

The main line was very important for the city of Georgetown, which was its major supporter, while other communities such as Batavia and Felicity were rather ambivalent towards it. Due to the sparse population of the southern ohio, the road (like most interurbans) never saw stellar revenues, but it held its own longer than most in the area. Passenger counts were a respectable 1 million in 1912, which put the CG&P between the stronger IR&T Rapid Railway Division and the weaker Cincinnati, Milford & Blanchester. While passenger operations were switched to electric equipment in 1902, they continued to operate steam freight trains partly due to bad experiences with electric box motors and locomotives. However, a fatal accident where a steam freight train and an electric passenger car collided head-on prompted the forced retirement of all steam service in 1915. In 1917 the troublesome Donham Avenue viaduct was removed since the Pennsylvania/Little Miami Railroad raised their tracks through Columbia-Tusculum, creating overpasses at Delta and Stanley Avenues. The IR&T and CG&P financed construction of a track extension on Kellogg Avenue from Donham to Stanley Avenue, where the new connection to the street railway would be made. By 1918 the rental fees paid to the street railway to allow their California and Coney Island cars to reach downtown became too expensive however, and city service was ended despite the improved connection. They continued to operate a few cars to downtown for express freight service, but this was terminated in 1922 when the IR&T was abandoned and the broad gauge tracks on Kellogg Avenue (and perhaps on Carrel Street as well) were torn up. Presumably the California branch was converted to standard gauge in 1918, but broad gauge cars may have kept running to Coney until 1922. Keep in mind there was still dual standard/broad gauge track in place between Carrel Street and the waterworks, and the connecting track in Carrel to the IR&T on Kellogg was broad gauge only. It appears that the third broad gauge rail was left in place along parts of the California branch (specifically on the Lick Run Trestle, perhaps as a guardrail) until abandonment in the 1930s. After the 1922 closure of the IR&T and no more connection to the street railway, any remaining broad gauge equipment was converted to standard gauge.

In 1923 the company was purchased by Lawrence Van Ness, someone who ultimately was more interested in building up his portfolio of lucrative electricity franchises than in operating railroads. When he purchased the CG&P he instituted a number of changes to streamline operations and improve profitability. Specifically, closing down the Lake Allyn power station and purchasing electricity from Union Gas & Electric, and converting to one-man car operation. In 1924, he moved the terminal from Carrel Street to a new loop on the west side of Stanley Avenue across from Stacon Street. Although the IR&T had been abandoned and torn up two years earlier, the CG&P was still able appropriate the IR&T franchise agreement with the city to operate over Kellogg Avenue. A new track was built along the side of the street, which had to be moved in 1927 when the street was widened and paved. It appears that a new connector track a short ways south of Carrel Street was built as well, since the old broad gauge track in the middle of Carrel was likely scrapped in 1922 when the IR&T was abandoned. A two-story stucco station and office was built at Stanley Avenue, and even though there was no physical connection to the street railway like there was in 1917-1922, the new loop was just on the other side of the railroad embankment from the East End car line, instead of a block away and past a grade crossing of the Pennsylvania Railroad. After this point, Carrel was only used for car storage and freight, and all passenger cars terminated at Stanley.

|

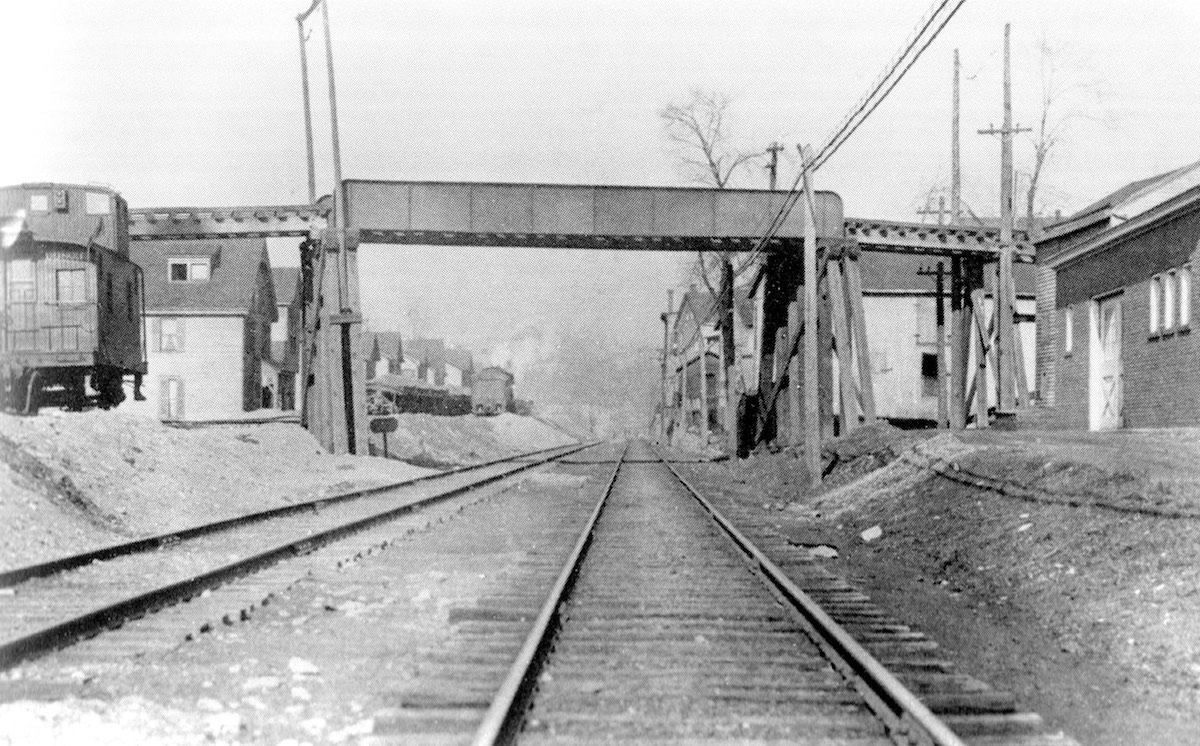

Tracks from 1925 on Kellogg Avenue at Two Mile near Coney Island, just three months before abandonment of the California branch east of the waterworks. From the University of Cincinnati Library Digital Resource Commons, Street Construction and Improvements collection. |

In 1925 there was a slight rerouting of the California branch as well. The 1902 extension to Coney Island was built through California via Lineman Street, jogging west southwest at what is today the I-275 Combs Hehl Bridge approach, terminating at the western tip of Lake Como. This was an ok entrance to the amusement park, but the new race track that was opened in 1924 was too far away from the west gate to walk to. The CG&P built a new track between California and Coney Island's main entrance at Sutton Road in time for the July start of the 1925 racing season. New track was built from about where Lineman Street ends in today's RiverCity Sports Complex on a tangent towards Kellogg Avenue. It intersected and crossed Kellogg at a slight bend in the road that remains under the I-275 overpass and ran along the northeast side of Kellogg for about 500 feet before crossing back to the southwest side of Kellogg at Two Mile (which used to intersect southeast of today's ramps to and from I-275 eastbound). It's anyone's guess why the track had to cross Kellogg, because that initially made the city hesitate to grant permission for the new routing. After returning to the southwest side of Kellogg, the track ran a good distance off the side of the street, and it appears to overlap the current location of the entrance ramp into Coney Island. How far towards Riverbend the new extension went is unclear, but it may have only gone just past the main entrance to Coney Island, ending at a loop somewhere in the grass next to the Sunlite Pool. Despite the more convenient terminal location and rerouting of the California branch, the end came rather quickly, as passenger and freight traffic dropped off markedly in the late 1920s and 30s.

Reorganization of the company as the Cincinnati-Georgetown Railroad and abandonment of the Coney Island branch east of the waterworks came in July 1927 (barely two years after rerouting) while the company retrenched and tried to economize the remainder of their operations. Nevertheless, auto competition and the Great Depression took its toll, on top of Lawrence Van Ness' increasing interest in electric service instead of railroading. As the Depression set in, branch lines were cut and mainline service reductions started in 1933. The Felicity & Bethel, for instance, saw so little patronage that the motorman who operated the car on that line routinely fell asleep at the controls, leading to a few minor wrecks before he was finally fired. By 1936 the CG&P was out of business and its assets were scrapped, with most of the electric lines going to the Union Gas & Electric Company. There had been talks for years of the Cincinnati Street Railway taking over the route to Mt. Washington and/or California, since the residents of those neighborhoods wanted a flat 5 cent city fare and more frequent service since the CG&P and the IR&T ran cars only about every 2 hours due partly to their overlapping service area. The Cincinnati Street Railway determined that there was not enough population in either neighborhood, and the line would operate at a loss after extensive repairs and the change to broad gauge were finished, even if the property was obtained for free. The city of Cincinnati did purchase the western end of the CG&P however, though only for freight service to the California waterworks. They abandoned the electric power and bought a gasoline switcher for use on the line. Even this proved too much of a hassle, and the last freight run was in 1943. The spur off the Pennsylvania/Little Miami Railroad tracks at Carrel Street remains to this day however, and a chemical loading platform on that spur was still in use by the water works (and possibly the adjacent Metropolitan Sewer District treatment plant) into the late 20th century.

|

The Lick Run Trestle over Kellogg Avenue. Note how the street is split around the support pier. From the University of Cincinnati Library Digital Resource Commons, Street Construction and Improvements collection. |

There's nothing to see of the CG&P's later terminal at Stanley, as both that street and Kellogg Avenue have been widened, and the loop and terminal building are long gone. There's more to see in Columbia, also the location of an old Pennsylvania/Little Miami Railroad station at Carrel Street. There is still a railroad spur at Carrel Street leading towards the aforementioned loading platform which has been restored with historical plaques and is now a trailhead for the Ohio River Trail. The rest of the yard is just overgrown woods. Right next to Lunken Airport there is a low flood wall that used to be a wooden CG&P trestle that was eventually filled with earth. The track ran straight to the Little Miami River, though construction of the primary runway 3R/21L in the 1960s necessitated relocating the flood wall. Where the recreational trail takes a sharp 90º turn near Signature Engines and Waypoint Aviation, the fill ends and a long wooden trestle continued ahead. A stone bridge pier off the recreational trail near the river at the other side of the runway marks where it used to cross. In the winter, one can see the right-of-way climbing up and winding around the hill at the edge of California Woods Preserve. About half way up the hill to Mt. Washington, the branch line to Coney Island split off from the main line at California Junction, which is also the name of the hiking trail that runs along the roadbed. There's some interesting stuff left here under the old junction, just east of a sharp bend in Kellogg Avenue. Some foundation piers for the trestle are still embedded in the hillside, electric sub-transmission lines follow the route, and there is an odd road loop on the south/eastbound side of the street that sort of looks like a bus or streetcar loop. This was actually the eastbound lanes of Kellogg Ave. There was a fat steel support column for the railroad trestle above which split the lanes of the road around it. Apparently they only recently fixed it and abandoned the old outer lanes, leaving this "loop" that's now barricaded off. On the waterworks property itself most of the railroad has been removed around the treatment facilities. However, tracks leading to the River Station pump house still exist. There is also a network of 18" narrow gauge tracks that were used for hauling coal and ashes around the property. Permission is required to enter the waterworks facility, and none of the trackwork is visible from Kellogg Avenue. There's not much to see of the rest of the branch line in California except grading, and nothing remains near Coney Island due to the construction of I-275.

The main line continued the climb up the hill back in California Woods. There's a road called Moon Valley Lane that leads to the right-of-way. This road ends with a driveway to the front and to the left. The driveway to the left is the right-of-way, and if you look to the right the right-of-way follows a little cut in the hill and bends to the south. There's nothing to see along Apple Hill or Salem Roads which were bridged by wooden trestles, but north of here the right-of-way is a bit more evident. The old Mt. Washington station is on Sutton Road, it's an American Legion Hall now. Behind there is an electrical substation and a parking lot and a fence line that follows the rail bed. The line then curved southeast and wiggled around a bit before shooting east-northeast towards Clermont County. Because of suburban development, there's nothing much left to see except some houses that are older than the rest. The CG&P and the New Richmond Branch of the C&E crossed each other and Clough Pike in a small valley at the border between Hamilton and Clermont Counties. There's some streets and driveways between here and the I-275/OH-32 interchange that mark the route, although nothing at all remains in Eastgate due to road construction and more suburban strip development. Much evidence remains beyond Eastgate however, as the area becomes more rural. Olive Branch and the former Lake Allyn are still relatively unscathed (though Lake Allyn itself has been drained due to sediment buildup). Jeff Wood has provided several pictures of the line through Clermont County and points east.

Main Line Photographs from Columbia-Tusculum to Russellville

California Branch Photographs from California Woods to Coney Island

Batavia Branch Photographs from Olive Branch to Batavia