Historic photo of the IR&T downtown terminal building at 419 Sycamore Street. Now the location of the First Financial Center.

IR&T - Interurban Railway & Terminal

|

Historic photo of the IR&T downtown terminal building at 419 Sycamore Street. Now the location of the First Financial Center. |

Three 5'-2 1/2" lines out of Cincinnati comprised this company. The first was built along the Ohio River to New Richmond (19 miles) in 1902 by the Cincinnati and Eastern Electric Railway. The second, the Suburban Traction Company, opened a line to Bethel (32 miles) in June 1903, and the third, the Rapid Railway, finished a line northeast to Lebanon (33 miles) in October of the same year. The three companies were consolidated in 1902. This company was also badly damaged by the flood of 1913, and in 1914 went into a receivership from which it was never removed. The Bethel line was particularly weak, since most of it was within sight of the Cincinnati Georgetown and Portsmouth, a somewhat stronger company. The IR&T Bethel line had the advantage of entry into the downtown area over the Cincinnati Street Railway, but this was not enough to save it, and it was abandoned in 1918. The remaining lines to Lebanon and New Richmond were abandoned in 1923. (From: Hilton, George W. and John F. Due, The Electric Interurban Railways in America. Stanford University Press, 1960)

The Interurban Railway & Terminal Company was meant to address the issue of lackadaisical interurban construction for a city of Cincinnati's size and prosperity. The earliest all-new interurban in the region was the Cincinnati, Lawrenceburg & Aurora, constructed in 1900, and pre-existing steam railroads like the Cincinnati, Georgetown & Portsmouth and the College Hill Railroad/Cincinnati Northwestern Railway weren't electrified until 1901 or 1902. All of Cincinnati's interurbans were built or electrified between 1900 and 1906, whereas other cities as nearby as Dayton saw interurban construction starting as early as 1890. The operators of the Cincinnati Street Railway prior to about 1903 were not interested in allowing interurbans to use their tracks to reach downtown, preferring to run city cars to meet the interurbans at the end of the line at transfer points. The broad gauge tracks and dual overhead wiring used by the street railway also posed challenges for interurbans. The city's narrow streets and tight curves also posed car design challenges for companies wanting to operate over the street railway, since interurban cars were usually longer and wider than streetcars. All of these obstacles delayed interurban construction.

In 1900 a syndicate was formed to construct broad gauge interurbans serving the north and eastern territories of the Cincinnati region. Headed by George R. Scrugham, four separate companies were formed to undertake construction. The Cincinnati & Eastern Electric Railway would run from Columbia-Tusculum to New Richmond; the Suburban Traction Company would branch off the eastern division at Coney Island and run to Bethel; the Rapid Railway would run from Norwood to Lebanon; and the Interurban Terminal Company would construct their downtown office and station at 419 Sycamore Street. This was a handsome 6-story building with internal tracks and a waiting room on the first floor. Company offices were upstairs, with additional floors of offices rented out to various tenants. The top two floors of the building were destroyed by a fire on March 6, 1913 and were never rebuilt.

Believing a proper downtown terminal was essential in the development of interurban passenger and freight business, the syndicate introduced a measure, known as the Roudebush Bill, to the Ohio Legislature, which provided the ability for interurbans to condemn right-of-way inside municipalities, including streets, for terminal purposes. This bill was fiercely opposed by municipal street railway companies, but it allowed the syndicate to negotiate with the Cincinnati Street Railway for access to the Sycamore Street station, and the bill was allowed to die. It wasn't smooth sailing from that point however, for the street railway company would retain three of every five cents collected by the interurban for city passengers, and the IR&T would have to pay for all changes to tracks and curves necessary for their cars to operate through the city. The idea of adding a third rail and operating standard gauge cars was rejected as the syndicate did not feel the ability to interchange traffic with steam freight railroads was worth the added investment.

Construction of IR&T tracks was relatively lightweight, especially on the eastern and suburban divisions into Clermont County, which were almost entirely built on public highway rights-of-way. The rapid division to Lebanon had a lot more private right-of-way, because most of it was directly adjacent to the Cincinnati, Lebanon & Northern Railroad from which it siphoned away nearly all the local traffic. With a minimal amount of grading and roadbed to build, the company poured more resources into their buildings. The downtown Cincinnati terminal, the carbarns, power houses, and substations were rather lavish affairs compared to other local companies, all of which were designed by Scrugham with assistance from the Cincinnati architecture firm of Werner & Adkins. The only really pedestrian major building was the rapid division's power house in South Lebanon, which was relatively hidden away in the woods. Scrugham was also heavily involved in overseeing construction of the buildings as well as the tracks and bridges.

Due to the tight spacing and sharp curves on the street railway, the IR&T's cars were smaller than most interurbans. They were more like the street railway cars, with short trucks, sitting low to the ground, and using a monitor roof that stops before the ends of the cars rather than a more railroad-like clerestory design that tapers down to the car's front and rear windows. 36 cars were purchased from the St. Louis Car Company for the system, 26 of which were passenger cars with smoking compartments, and 10 of which were combines with passenger and express freight areas. Three freight box motors, four open summer cars for excursions, three work cars, and one one supply car rounded out the company's initial roster. All cars were equipped with two trolley poles to operate on the street railway's electrical system. The negative pole would be raised or lowered at the city limits, and they had a switch that could allow the negative pole to be used in the country in case the positive pole broke.

Known colloquially as the Black Line due to the dark paint scheme on their cars, the Interurban Railway & Terminal Company was created on November 4, 1902 from the consolidation of the aforementioned four firms, while both the suburban and rapid divisions were still under construction. There was $2.5 million in capital stock with an equal amount of bonds issued. The managers of the company, despite their insistence in serving Coney Island, did not believe it was good policy for electric railway companies to own or operate amusement parks or other attractions. This lack of diversification may have been a factor in the early demise of the company. On the other hand, they developed a robust freight business somewhat unexpectedly, requiring a hurried establishment of express agencies, special car runs, and construction of loading platforms. This was mostly less-than-carload (LCL) freight, handled either in baggage compartments of their combine cars or in dedicated box motors. Such freight hauling faced serious competition from trucks by the 1920s. That said, the IR&T did extensive business in milk, with special cars operating between the French Brothers Dairy in Lebanon and downtown Cincinnati to serve the city hospitals with 1,500 gallons per run. After only six months in operation, the freight business yielded more net profit than the passenger business.

Columbia - New Richmond

1902-1922

Broad Gauge

Constructed by the Interurban Railway & Terminal Co., 1902

Abandoned, 1922

|

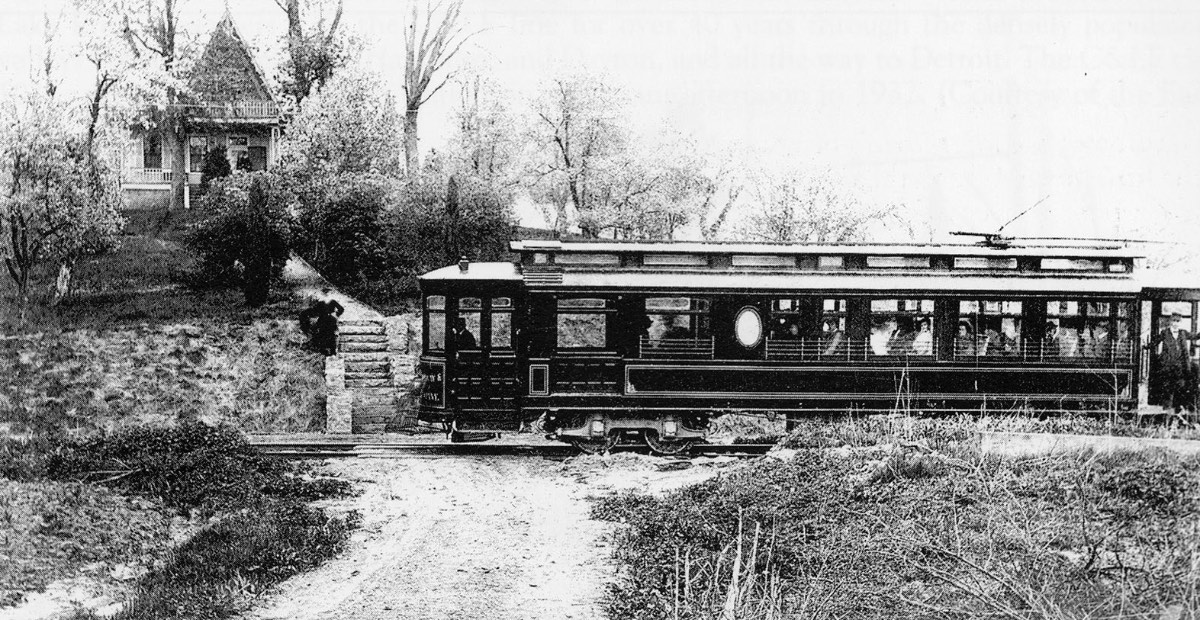

This IR&T Eastern division car has stopped at the foot of Eight Mile Road and Kellogg Avenue in 1903. The man with the fuzzy beard standing on the steps is identified as the photographer, who rigged the camera to automatically take the picture while the car stopped in front of his house. From the Earl Clark collection. |

Not to be confused with the Cincinnati & Eastern Railroad, predecessor to the Norfolk & Western's Peavine route that also had a branch to New Richmond, this was the first IR&T line placed under construction on September 15, 1900 and completed on October 12, 1902. While the terminus in New Richmond was the ultimate goal from the beginning, establishing service to Coney Island was of the utmost importance. By this time the city of Cincinnati was constructing their new waterworks in California, and the CG&P was building an extension of its spur to the waterworks into California and Coney Island as well. Both companies were eager to get in on this lucrative traffic.

While the CG&P benefited from the city building the Lick Run Trestle over Kellogg Avenue so they could reach the waterworks, the IR&T benefited too. The area of Kellogg Avenue near Lunken Airport, then called Turkey Bottom, was and still is prone to flooding from the Ohio River. The city required the company to raise the grade of Kellogg Avenue and ensure the new embankment wouldn't wash away. They were able to achieve this by redistributing the excavated rock and shale from the huge new gravity tunnel being constructed between the water treatment plant in California and the pumping station also under construction on Eastern Avenue next to St. Rose Church. The pumping station was located there instead of at the treatment plant in part to put it in a more central location relative to the city as a whole, but also because the technology and funds weren't available at the time to build multiple large pressurized water mains under the Little Miami River, which lacks the stable bedrock cover necessary to prevent the pipes from blowing out. This 10-foot diameter tunnel is over four miles long, and the excavation allowed Kellogg Avenue to be raised to a minimum elevation of 55 feet.

Both the eastern and suburban divisions shared a carbarn and power house, which were located on Kellogg across from Coney Island. The carbarn had six bays and a three story office wing on the left, totaling 76 feet wide and 253 feet deep. The building was quite elaborately detailed, especially the office area, and it was identical to the rapid division's Deer Park carbarn with the one exception that the Deer Park building also had an electrical substation. The power house, another sumptuous structure, was initially built just to handle the eastern division, since it was uncertain if the suburban division would be built at all. The eastern division was fed with direct current at 500 volts straight from the power station, due to the relatively short run of four miles west to Columbia-Tusculum and a nearly flat 13 miles east to New Richmond. When the longer and hillier suburban division was built, the building was enlarged and more boilers and generators were installed. These additional generators fed the suburban division with 3-phase 10,000 volt alternating current which was stepped down to 650 volt direct current at substations in the power house itself, as well as at Forestville and Amelia. Most of the space in these substations was taken up by the rotary power converters, but they also provided passenger waiting rooms, a freight room, and on the second story an apartment for the attendant's family.

The Cincinnati & Eastern division connected with the East End car line of the street railway at Donham Avenue. The city built a single track viaduct over the Pennsylvania/Little Miami Railroad tracks at this location using a gauntlet track that eliminated the need for switches, but it only allowed cars to pass in one direction at a time. The CG&P would also use the Donham Avenue Viaduct until the railroad was raised above street level in 1916/1917 allowing new connections to be built at Stanley Avenue. Due to expected heavy traffic to and from Coney Island, along with plans for the new Suburban division to branch off at Sutton at the entrance to Coney Island, the IR&T was built with a double-track main line from Donham Avenue out to Sutton. This made the single track viaduct an operational bottleneck since cars from both companies in both directions had to stop for fare inspectors to count passengers, to wait for streetcars to pass, and potentially also to check in with the dispatcher. After coming off the viaduct the tracks were in the middle of Kellogg until after the crossing of the Little Miami River. At a sharp bend in the road, the tracks the moved off the roadway to the east side, and they stayed there until approximately Rhodes Street in California, where they then moved back to the middle. The carbarn was located a few hundred feet west of Sutton with several tracks entering the property. There was a jumble of tracks at Sutton itself as well, with a double track spur into Coney Island, which had a loop near the end of the entrance road, where it makes a sharp turn today. A double track turned up Sutton for the suburban division and then merged to a single track for the climb up the hill. The single track main line continued east on Kellogg, with a couple of spurs into the power house property.

On the way to New Richmond the eastern division flirted with US-52. It diverged from the road in many places, and it ran on the road farther to the east, bearing to the north/east onto what is now Old Kellogg near Clermont County. Since the right-of-way was sandwiched between the river and the hillside, there were very few riders between California and New Richmond. Ridership on this line was only 357,000 in 1912, less than 1,000 passengers per day, making it the weakest interurban line in Cincinnati by quite a large margin. There was a small contingent of Kentucky residents that would cross the river by boat to take the traction line into Cincinnati, which was easier and less expensive than trying to catch a steam train on the C&O on the south side of the river. While this was praised by the promoters of the company, it could not have been a significant source of ridership. Regardless, the interesting terrain would have made for a beautiful ride. Because of that rough terrain, landslides, floods, street running, and later construction of US-52, there is very left to see, save for some stone bridge abutments over Twelvemile Creek at the northern edge of New Richmond. Any other remains along Old Kellogg seem to have been thoroughly extirpated.

Photographs from California & New Richmond

Columbia - Bethel

1903-1918

Broad Gauge

Constructed by the Interurban Railway & Terminal Co., 1903

Abandoned, 1918

|

Historic photo of the IR&T Suburban Traction line at stop 43 in Tobasco, looking west along Ohio Pike at the intersection of Mt. Carmel-Tobasco Road, circa 1905. Today this is the middle of the Ohio Pike I-275 interchange. From the Earl Clark collection. |

The Suburban division of the IR&T was placed under construction on April 15, 1901 and completed on June 1, 1903. This line to Bethel was in direct competition with the CG&P that had been around for 30 years already, though when construction started the CG&P was still mostly a narrow gauge steam railroad, which would be unable to compete with a more modern electric interurban. There was some question about whether the IR&T's suburban division would be built at all, but Scrugham was none too friendly with the owners of the CG&P, as they had fought over franchise agreements to reach Coney Island, and the CG&P was not amused at having competition for rather meager traffic. While Coney Island granted franchises to both companies, feeling that competition would lead to improved service, in reality it just divided up the traffic among the two companies. The same can be said for the remainder of the Suburban division, which served many of the same locales. Aside from the CG&P's northward route to Mt. Carmel and Olive Branch, the two companies tracks were virtually within sight of one another from Columbia-Tusculum all the way to the Suburban line's terminus in Bethel. The IR&T even proposed to build a branch line to Batavia, just as the CG&P had done, though this was never undertaken.

Despite the competitive nature of the two companies, they did cooperate on certain occasions, especially during floods or other disasters, helping each other to navigate washed out tracks and route passengers away from troublesome areas. One of the most contentious points, however, was the Donham Avenue Viaduct mentioned above in the eastern division's description. Because the two roads used this single track viaduct, going in both directions, it was frequently the site of delays. There are also reports of cars from one company blocking cars from the other company, and taking their passengers headed for Coney Island. When the PRR/Little Miami Railroad was elevated, both the CG&P and the IR&T made the connection with the streetcars a little further to the northwest at Stanley Avenue, and the viaduct was removed. While the IR&T connected with the East End streetcar line here, the CG&P built a loop and a stucco station/office building just south of the PRR viaduct, in the park opposite Stacon Street. Competition from the CG&P, as well as the rather sparse population along the line, made for a rather short life. There had been talks of the CG&P taking over portions of the route, but it never happened. Ridership in 1912 was only 553,000, worse than the C&C and CM&L, though better than the eastern division which had only 357,000 passengers that same year, but these were the two weakest lines in the entire Cincinnati system.

After branching off of the eastern division at Coney Island, the suburban division went up the hill along Sutton, generally staying off to the west side of the street, but snugged up against it for most of the way, and sometimes striking out on its own shallower route. Some of the grading and private right-of-way along Sutton is the first evidence of the IR&T at all near the city, since rebuilding of Kellogg Avenue in the late 1920s and again in the 1950s has removed any trace of what might have remained of the combined eastern and suburban route west of California. After a short diagonal cut through the neighborhood near Glade Avenue the tracks arrived at Mears Avenue, which it followed to the center of Mt. Washington. Upon reaching Beechmont Avenue, there was a stub that went north for a few blocks to serve the Mt. Washington business district. Originally the IR&T was supposed to build down Beechmont to Eastern Avenue after the city finished building their levee across the Little Miami River valley. The Beechmont route was going to be the main line for the suburban division, and the track down Mears and Sutton would be used to short-turn suburban rush hour runs and special charter trips, but the Beechmont extension was never built and the stub is as far as the track ever went.

From Mt. Washington east the IR&T track ran in the middle of Beechmont until a short distance west of Berkshire Lane, which is a steep dip in the road even today. Because of that, the IR&T built a wooden trestle at a higher elevation to ease the grade. The track moved to the south side of the road to accommodate this trestle. The intersection at Burney Lane one block farther was somewhat clumsy and misaligned at the time of the IR&T, so while the track stayed roughly straight, it actually moved to the north side of the road after making it through that intersection. The CG&P's Ellenora station was just south of here on Burney Lane as well. From here east the IR&T followed Beechmont Avenue along the side of the road. It was technically a private right-of-way, purchased from the Ohio Turnpike Company, with a small ditch separating it from the road, but it had the same appearance as typical side-of-the-road running. The tracks stayed on the north side of Beechmont/Ohio Pike until somewhere between Tobasco and Withamsville, at which point they crossed back to the south on the way to Bethel.

The Forestville substation, one of the more lavish buildings, was located at Asbury, now the location of an Arby's restaurant. While there are many utility poles all along Beechmont Avenue/Ohio Pike, they're not really a good indicator of the IR&T's location since the road has been so significantly widened. A notable exception is between England Club Drive and 8 Mile, were the power lines on the south side swing away from the pavement, indicating that the current road was straightened out from its old alignment. Immediately east of the I-275 interchange, Mt. Moriah Drive is the old route of Ohio Pike and the IR&T. This is likely where the tracks moved from the north to the south side of the road. East of Hamlet the IR&T had a sizeable wooden trestle over Back Run near Foozer Road, while Ohio Pike took a rather curvilinear path down into the valley and over the creek. Ohio Pike has since been realigned and placed on a high fill. Near East Fork State Park the highway takes a detour around its old alignment, and Old OH-125 through there is a decent representation of what all of Ohio Pike used to be like.

Photographs from California & Mt. Washington

Kennedy Heights - Lebanon

1903-1922

Broad Gauge

Constructed by the Interurban Railway & Terminal Co., 1903

Abandoned, 1922

|

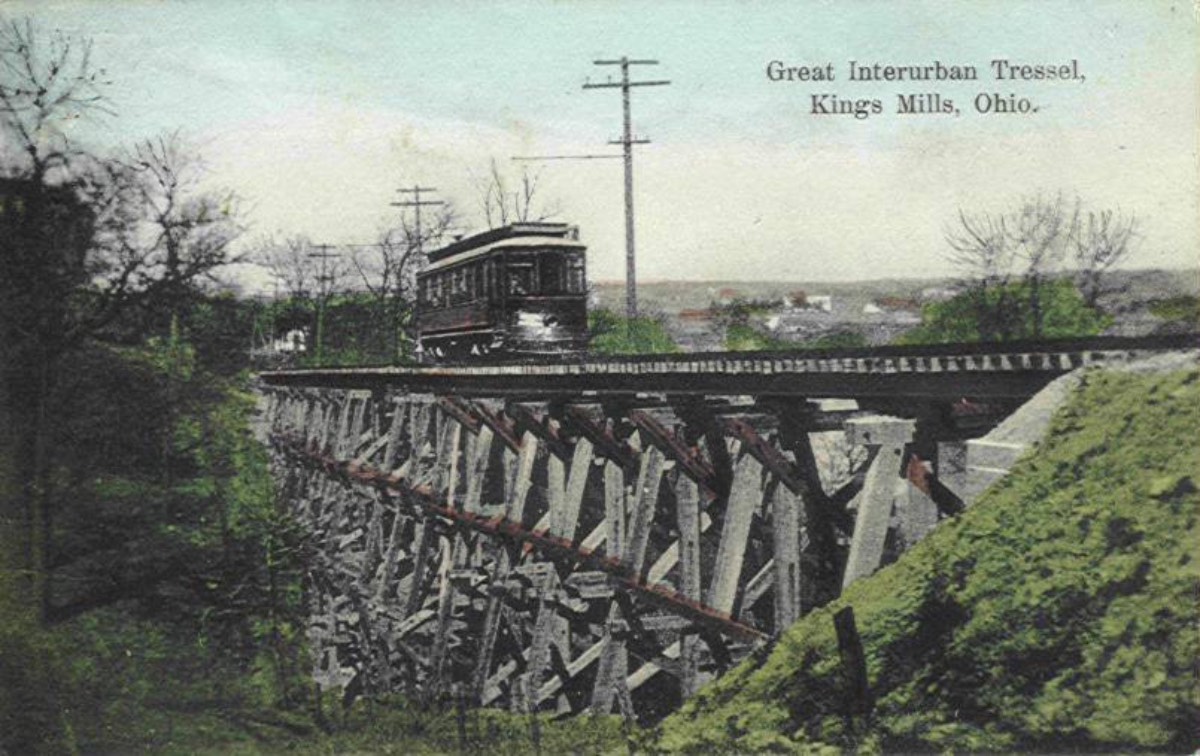

Historic postcard showing an IR&T Rapid Railway car and trestle in Kings Mills. This is looking north from Carter Park towards Turtle Creek and Mason-Morrow-Millgrove Road. |

Like the other IR&T lines, this one had a relatively short and uneventful life, though it was by far the strongest of the three routes. It began operations on October 1, 1903. As mentioned in the overall company history, this route took on a slightly different character than the suburban or eastern divisions, utilizing much more private right-of-way and paralleling the CL&N Railroad. The climb out of Norwood to Silverton is relatively easy, but the company had to widen the road to prevent their double track line from encroaching on the rest of the roadway. A lot of modifications were required to the existing street railway company tracks to allow the larger interurban cars to operate as well. The terrain between Silverton and Mason is gently rolling and required little grading, but the company had to contend with a steep descent into the Little Miami River valley between Kings Mills and South Lebanon. There's also a significant ridge the company had to breach in the final approach to Lebanon, requiring some cuts and fills along with steep grades. A branch line from South Lebanon (where the power plant was located) on the north side of the Little Miami River to Morrow was never built.

The Peters Cartridge Company in Kings Mills was a significant source of commuter business for the company. Because of the dangerous nature of the facility, buildings were scattered along the river, and employees were not allowed to live too close by. As mentioned in the overall company history, the French Brothers Dairy in Lebanon provided a robust business in milk to serve the Cincinnati city hospitals. 1.3 million passengers used the rapid division in 1912, actually beating out the CG&P and only a little less than the CL&A. This traffic was mostly siphoned off of the parallel CL&N Railroad which predated it by 20-some years and was operating slower steam service.

The rapid division ran on Montgomery Road, continuing past the end of the streetcar route, originally at Fenwick Avenue in Norwood, but later from Coleridge Avenue in Kennedy Heights after the street railway bought the tracks to extend their service. The route through Pleasant Ridge and Kennedy Heights was distinctive for the use of decorative iron poles and cross arms in the middle of the street. Similar to the eastern and suburban divisions, the line was built with a double track for several miles, becoming single track upon reaching Blue Ash Road in Silverton, and it paralleled the CL&N north through Deer Park along the west side of Blue Ash Road. Most of the route in this area is now used as parking along the street, and large power lines remain. The old carbarn is still standing at 7234 Blue Ash Road in a heavily modified state, now occupied by Stewart Industries. At today's Cross County Highway overpass the tracks ran on a diagonal through the neighborhood to Kenwood Road at Hunt Road to serve the center of Blue Ash. There was a short branch line to Montgomery, exactly paralleling a branch line for the CL&N, that split off the main line at Laurel Avenue.

Continuing north through Blue Ash, the track followed Kenwood Road to the CL&N crossing at Bell Avenue, where the tracks then paralleled the railroad on the way to Butler County. There's a noticeable tree line in the office park west of Deerfield Road at Corporate Drive where the IR&T deviated from the CL&N by a few hundred feet. Tracks snugged up to the CL&N until Tylersville Road in Mason where they moved onto Reading Road to Main Street in the heart of Mason, before striking out to the east on the way to Kings Mills with power lines representing the location. Some grading is visible in Kings Mills along Miami Street. The old Kings Mills station still remains on King Avenue. Behind there, the right-of-way is in a cut through the back side of Carter Park where the remains of the pictured trestle can be found. After reaching the bottom of the hill, the tracks crossed under the CL&N's Middletown & Cincinnati line, though nothing remains to be seen from there through the bulk of South Lebanon. The right-of-way splits off of Lebanon Road at Dry Run Road since the power lines follow the roadbed and not the street. There's not much to see on the way to Lebanon due to more recent construction of OH-48, however there are still tracks buried under the streets of downtown Lebanon. Cracks were telegraphing through the pavement on Mulberry Street as of 2006. This is one of the only instances of actual interurban era tracks remaining anywhere in the Cincinnati area.

Photographs from Pleasant Ridge to Lebanon